Podcasts

In March 2020 the exhibition curator Dr Alda Terracciano led a group of UCL postgraduate students in an oral history programme as part of the celebrations for the centenary of the Department of Information Studies. Acknowledging the wider, global context in which the department operates, students engaged former members of staff and alumni in a series of interviews exploring key issues faced by information professionals in their jobs. The aim was to stimulate a synergy between academia and the professional world, and increase students understanding of the job market by exploring critical areas of enquiry that have emerged from research and teaching at DIS and are reflected in everyday professional life.

Vanda Broughton

Vanda Broughton is Emeritus Professor of Library & Information Studies in DIS. She has a long association with the Department having been a post-graduate student in 1971/72, and a member of staff from 1997. Her research interests are in knowledge organization, particularly faceted classification, and she continues a substantial tradition of DIS expertise in this area. In her interview with Sae Matsuno held in two sessions on 9th and 14th April 2020, she talks about her working class family background, her long association with the department, its transformations over the past decades, and training students in Librarianship.

Interview - Part 1

Transcript

Sae Matsuno (00:00:02)

9th of April 2020, my name is Sae Matsuno and I’m remotely interviewing UCL Emeritus Professor Vanda Broughton from my home in London. This interview is part of the Department of Information Centenary project Geographies of Information. So before starting our interview, could you repeat your full name and say where you are right now?

Vanda Broughton (00:00:33)

I’m Vanda Diane Broughton and I’m in a place called Wickham Market, which is in Suffolk and it’s about 80 miles from London.

Sae Matsuno (00:00:48)

All right, do you still agree to participate in this interview?

Vanda Broughton (00:00:54)

Yes, of course.

Sae Matsuno (00:00:55)

Thank you very much. So this centenary project charts the history of the department, as well as its role in creating an international and professional workforce over the past decades. In the notes I read, you wrote, you had very long association with the UCL Department of Information Studies. So could you give me a rough timeline of when and in what ways you have been associated with the department.

Vanda Broughton (00:01:27)

I suppose my first contact with the department was when I was a student. That was in 1971 to 72. I’m trying to think, it would have… So the first time I came to the department would have been for an interview in 1971. So I was a student in 71 to 72. Then, when I graduated, I went to a research post at the Polytechnic of North London. But I came back to the UCL department from time to time, to talk about the research that I was doing. So probably during the 70s, I came and did some seminars and talks with students. Then, very much later on, I came back to the department, this would be in 1997, to do some paid research work on the Universal Decimal Classification. At that time, Professor Ia Mcllwaine was the editor in chief of UDC, and she invited me to do some research work. So I was employed as a, I don’t know what you would call it, a part time Research Assistant for two years. And then Professor Mcllwaine and her husband were due to retire. That was in 2000, and there was a lectureship being advertised to replace their teaching responsibilities. So in 1999, I applied for that lectureship and I was successful. So I came in October 1999, to a lecturing post, where I’ve been ever since. So that’s currently, that’s 23 years is that I’ve been in the department first, briefly as a researcher, and then for 21 years on the academic teaching side.

Sae Matsuno (00:04:01)

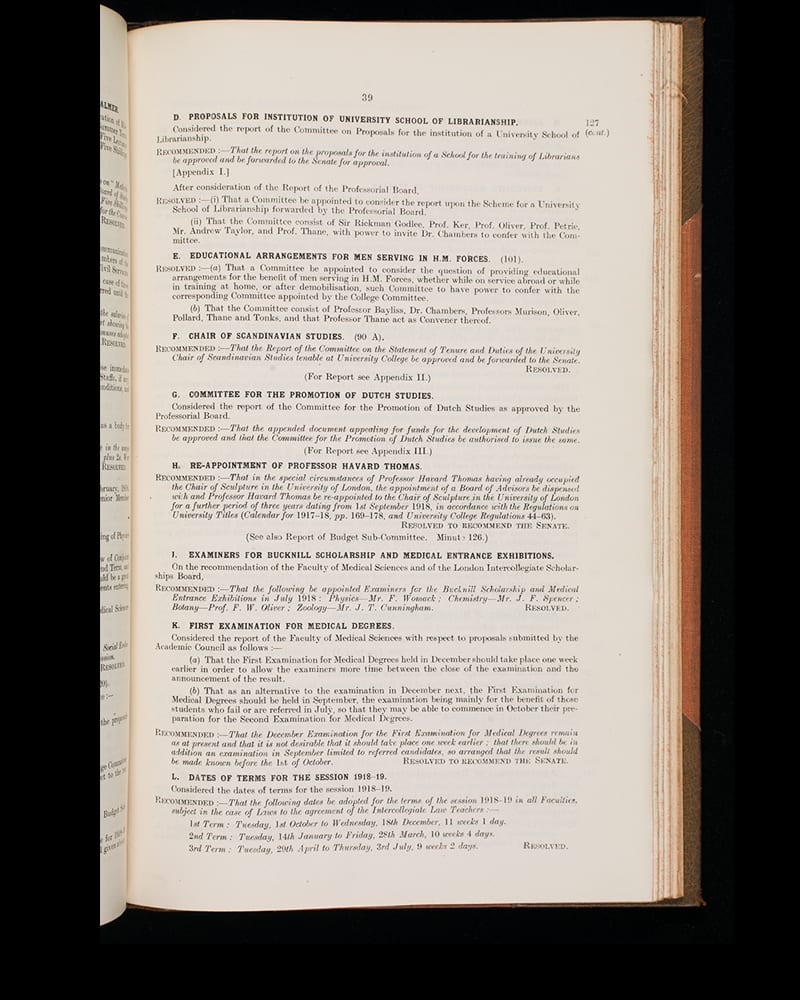

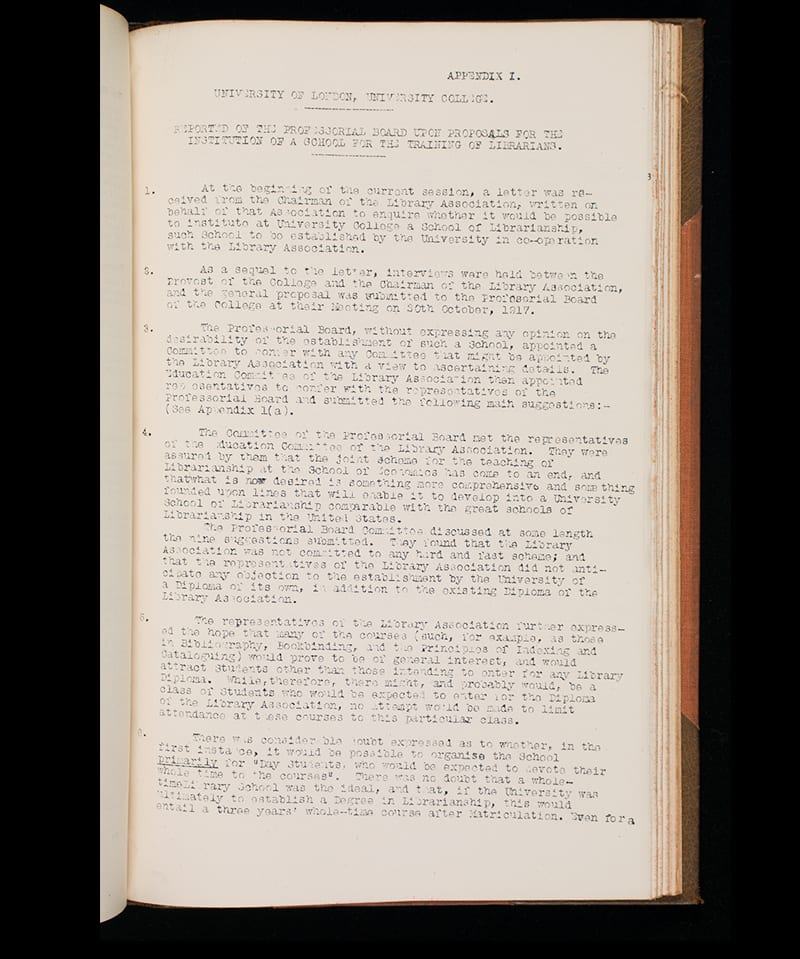

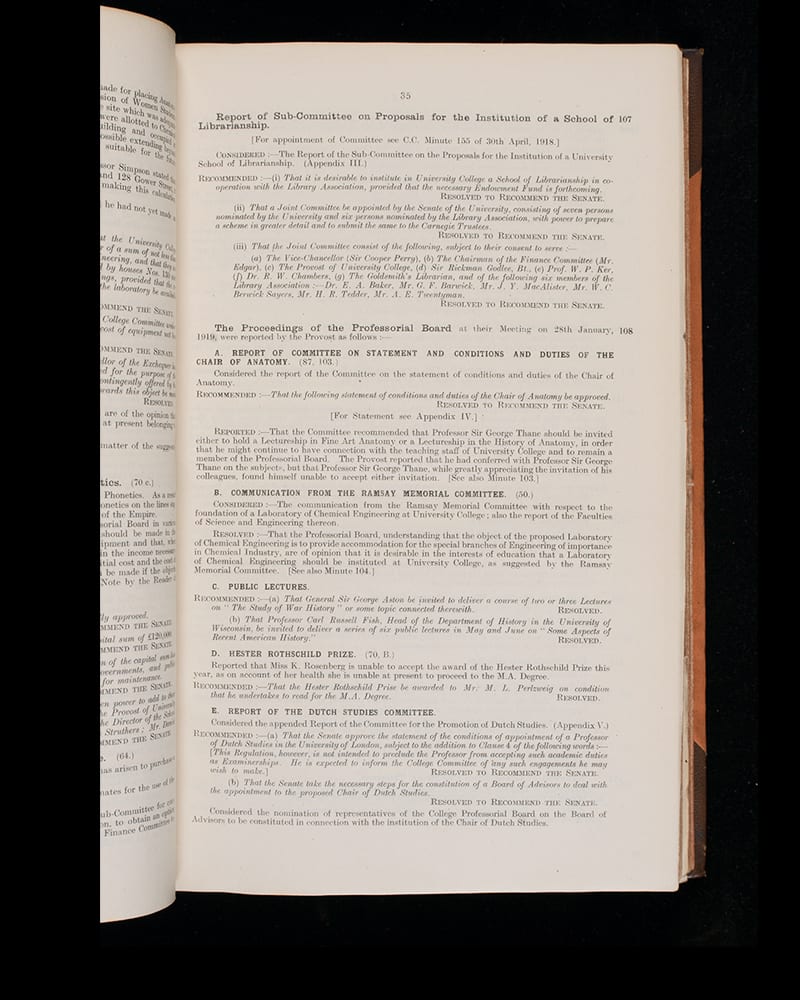

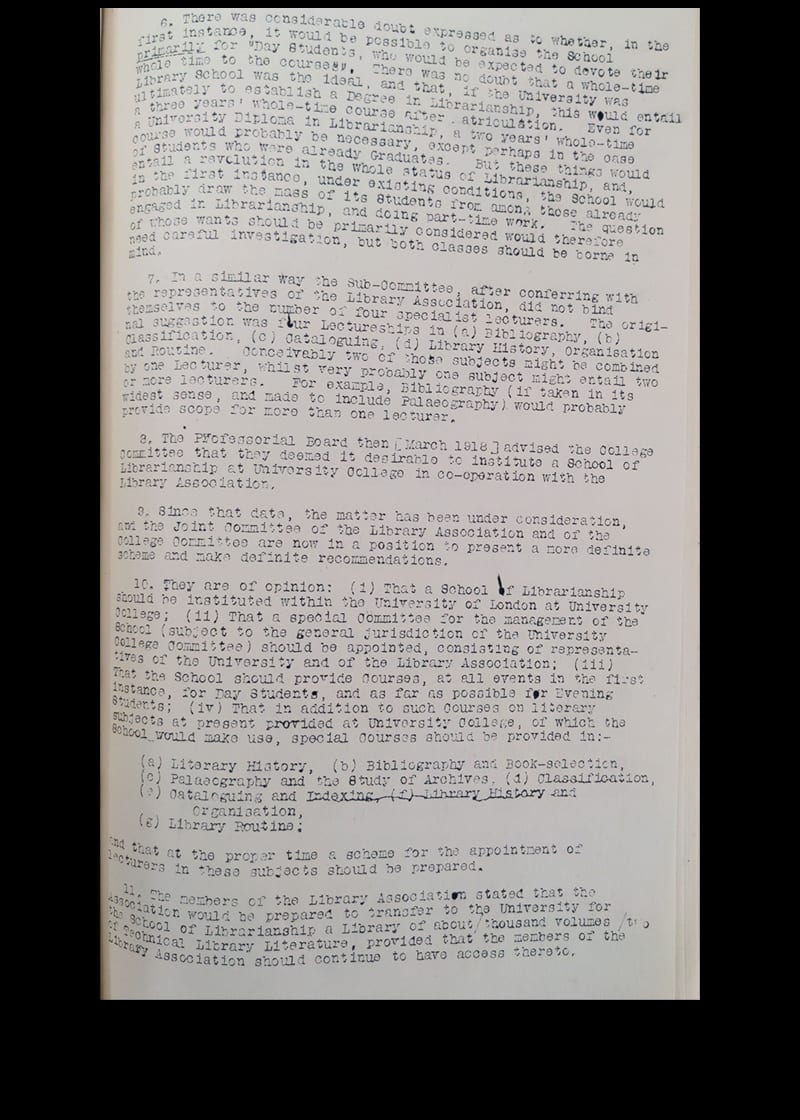

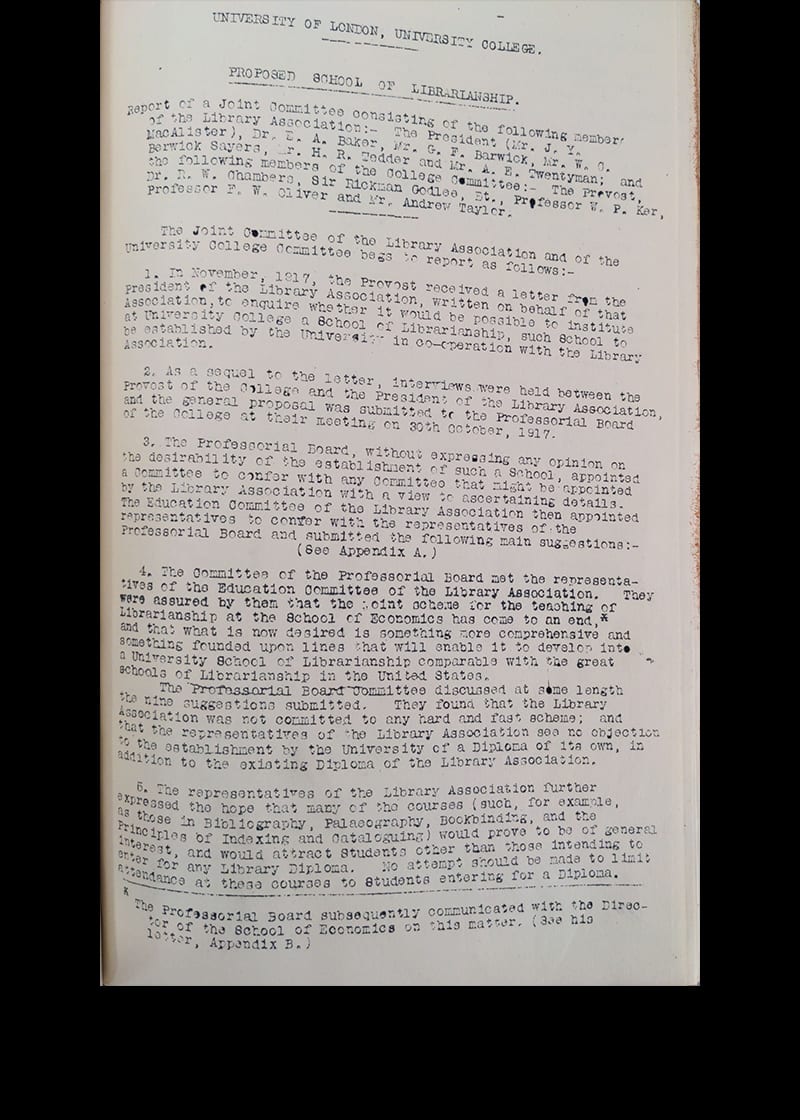

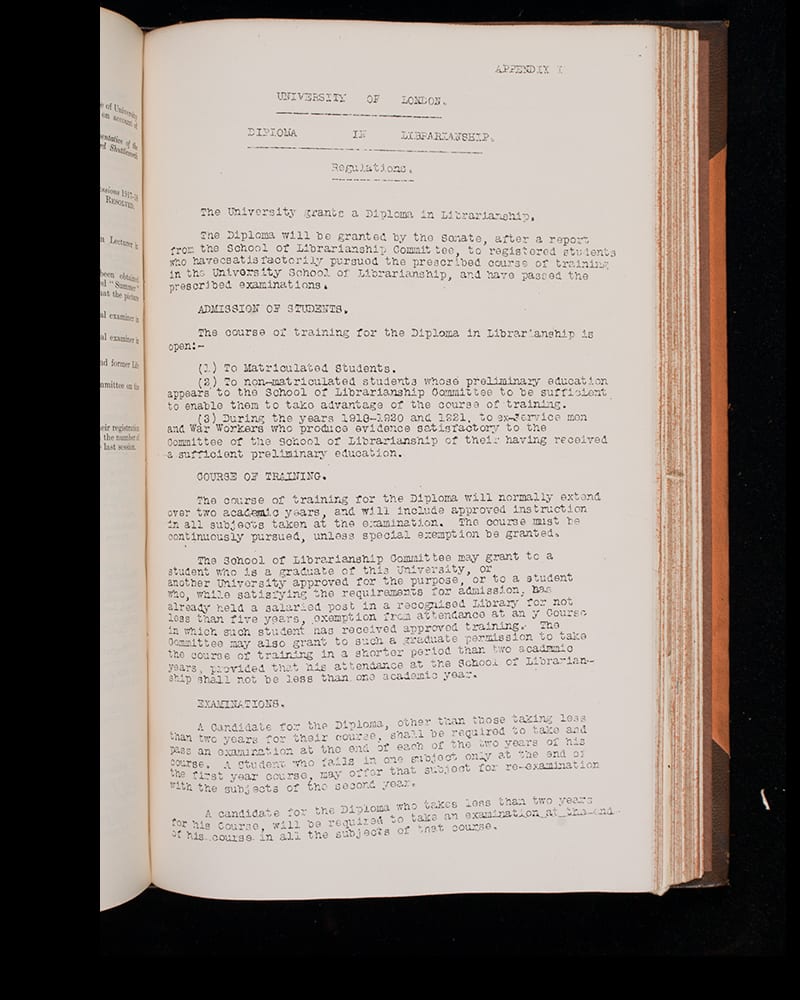

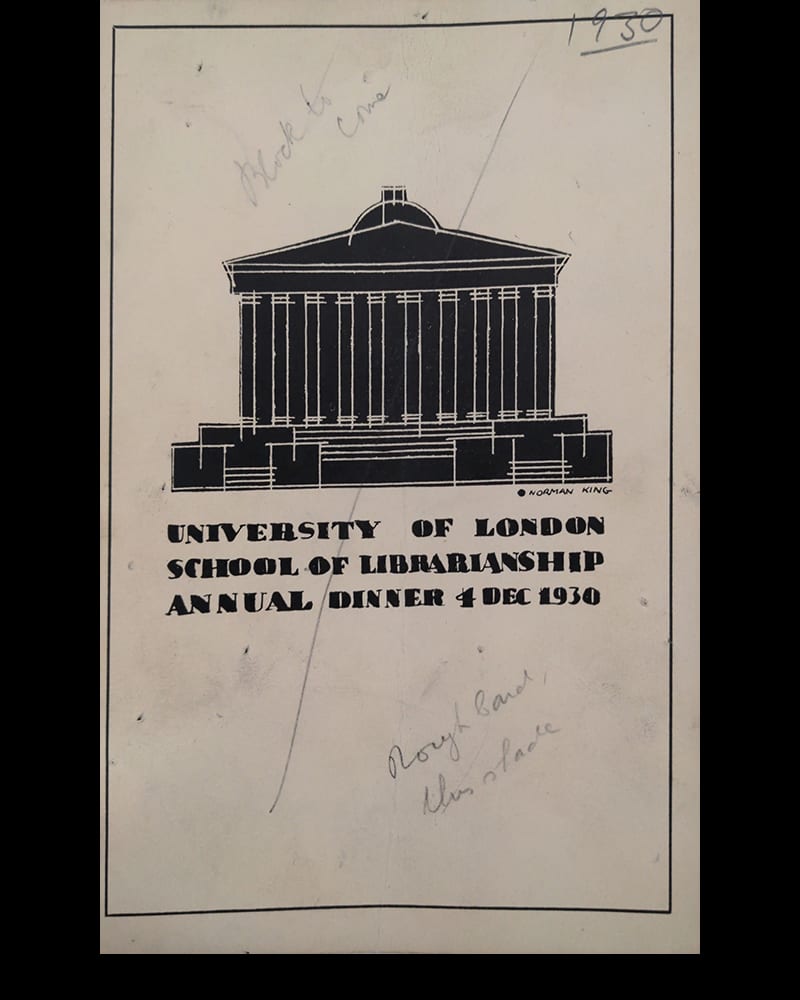

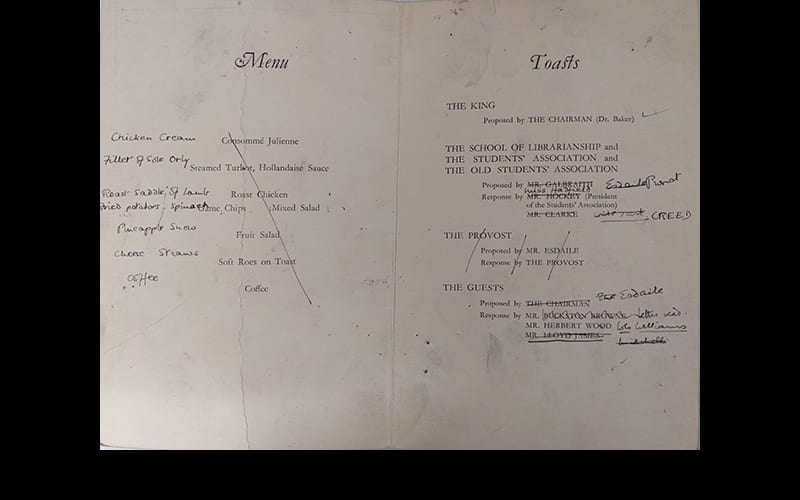

All right, well, that’s, that’s many years. And it’s still counting. That’s amazing. And so the department has changed its name several times in its history, starting as a School of Librarianship in 1919. Would you be able to guess some of these names? For example, when you were a student? Do you remember the name of the department how it was called?

Vanda Broughton (00:04:35)

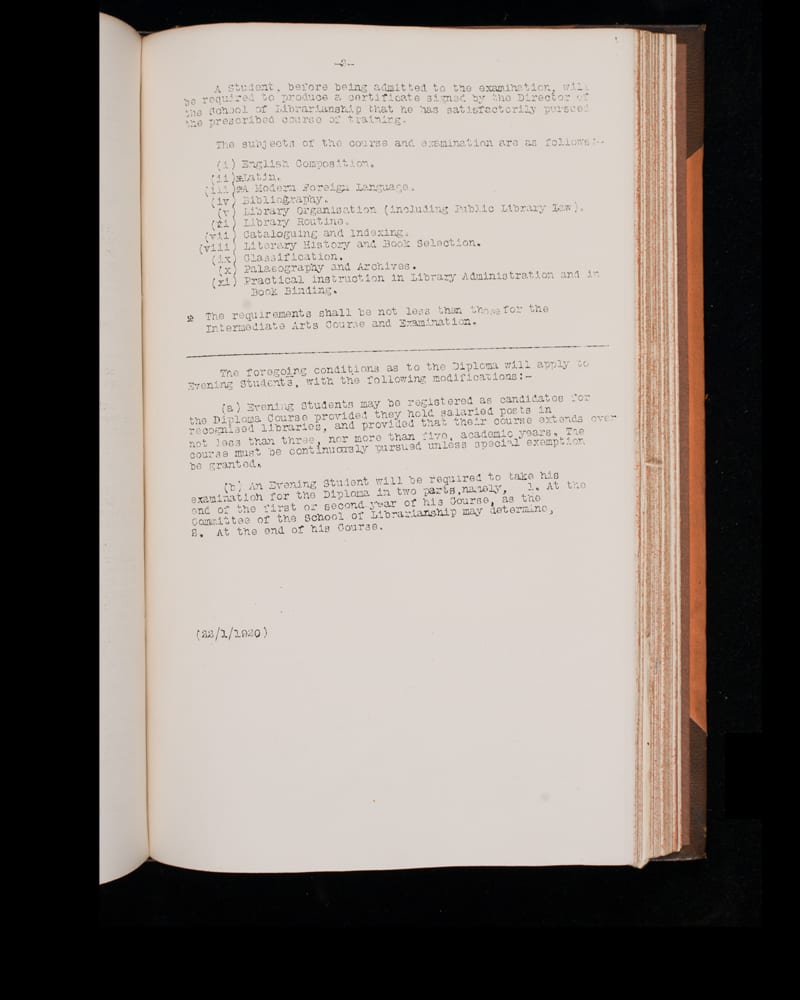

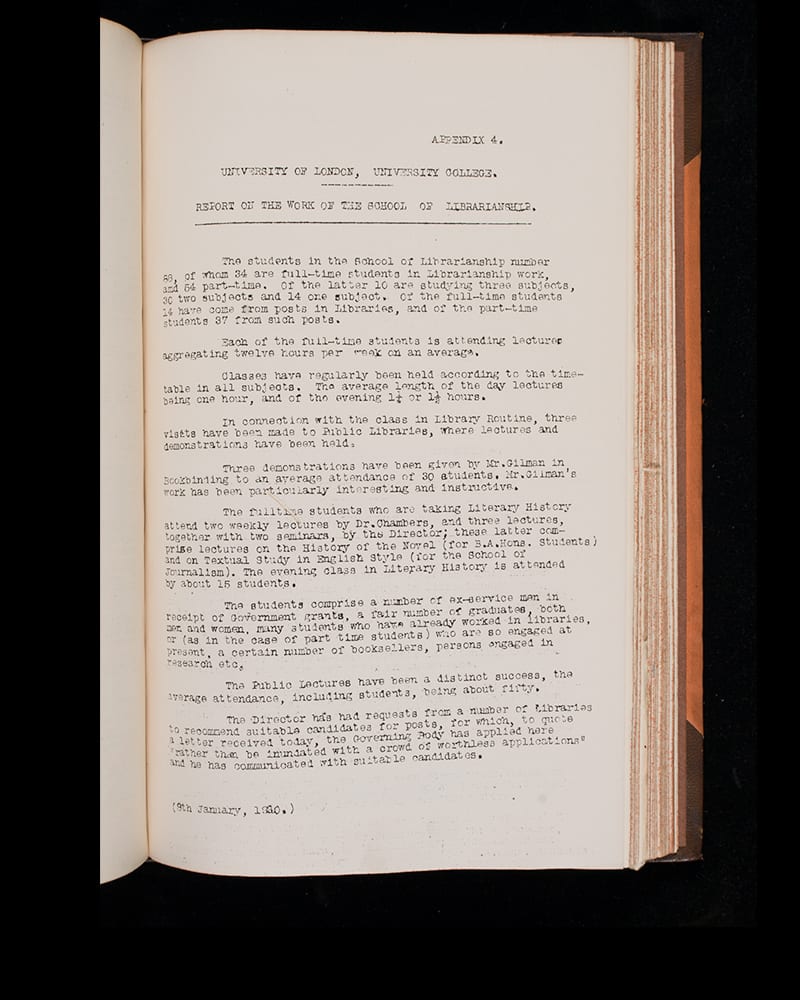

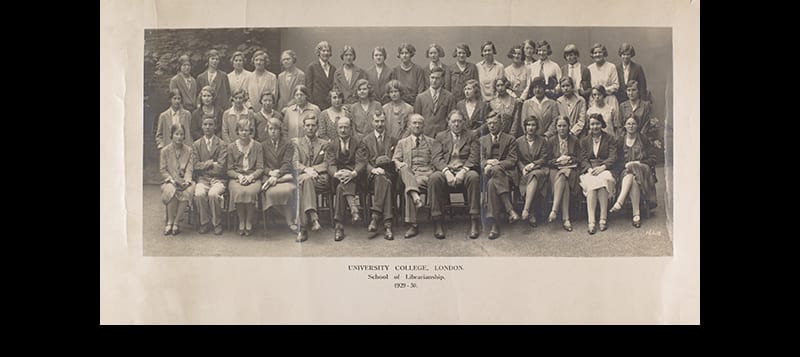

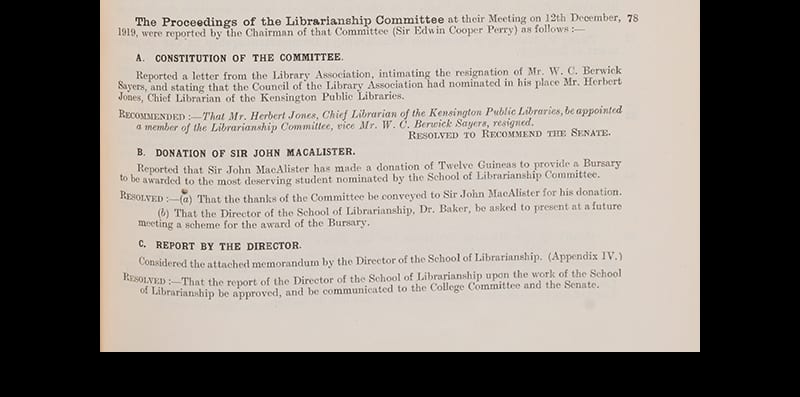

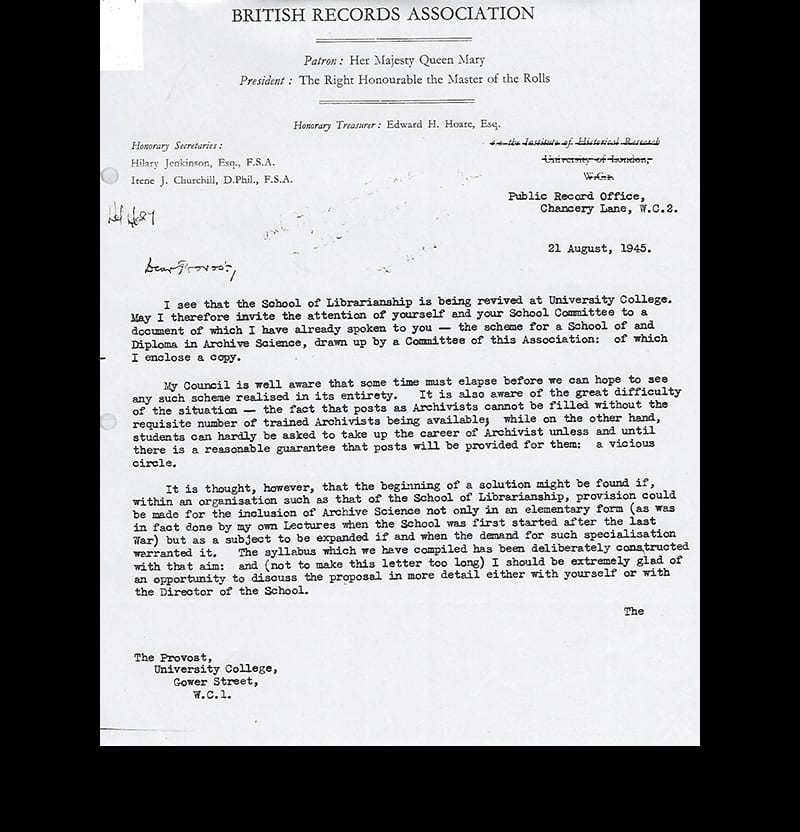

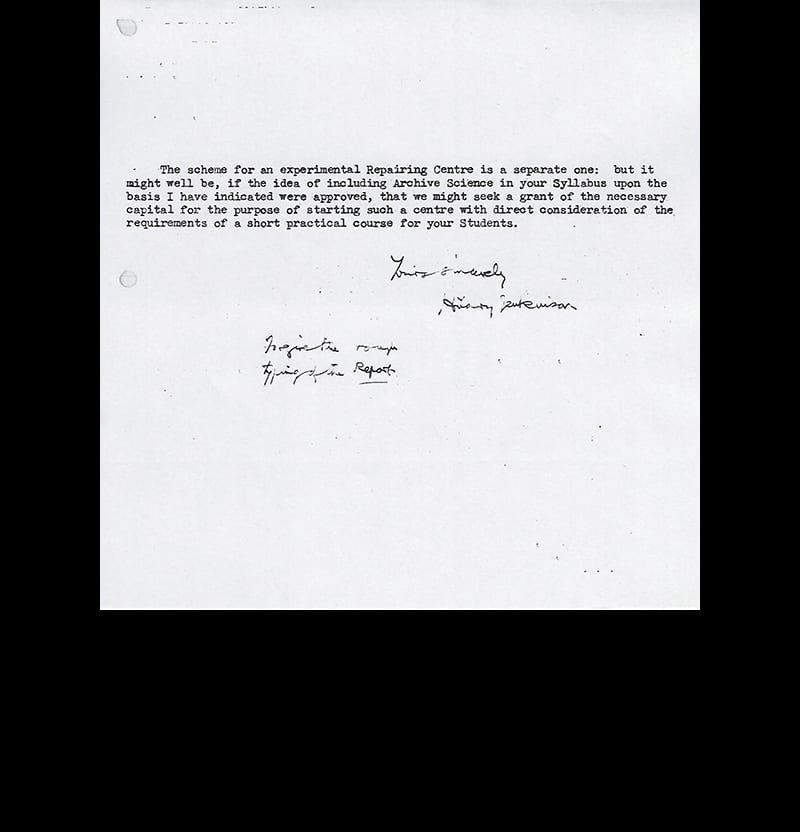

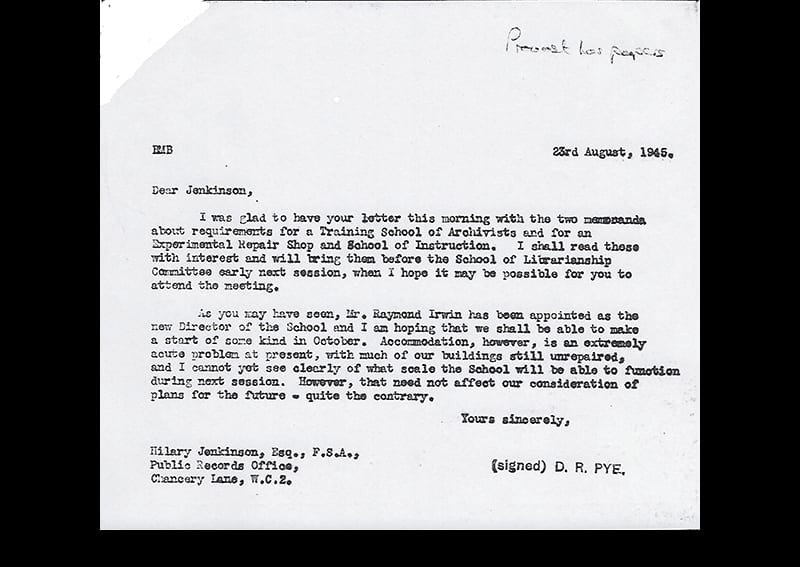

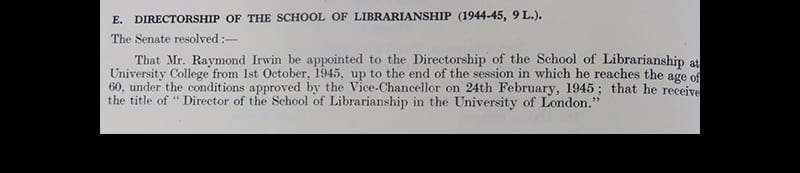

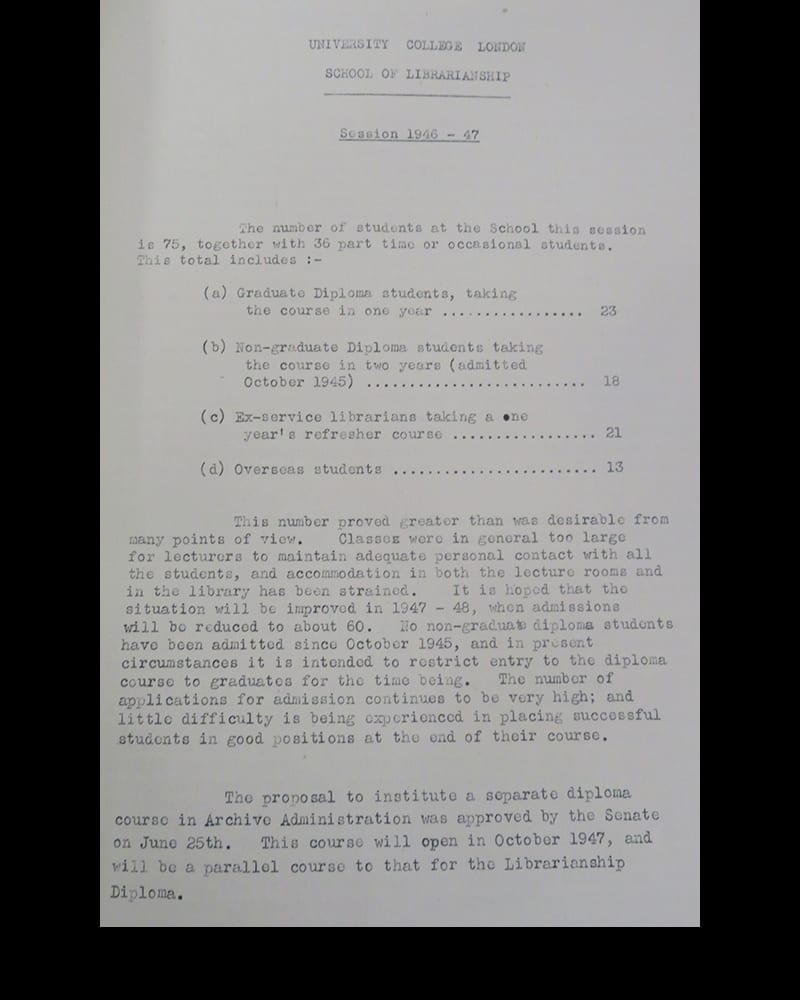

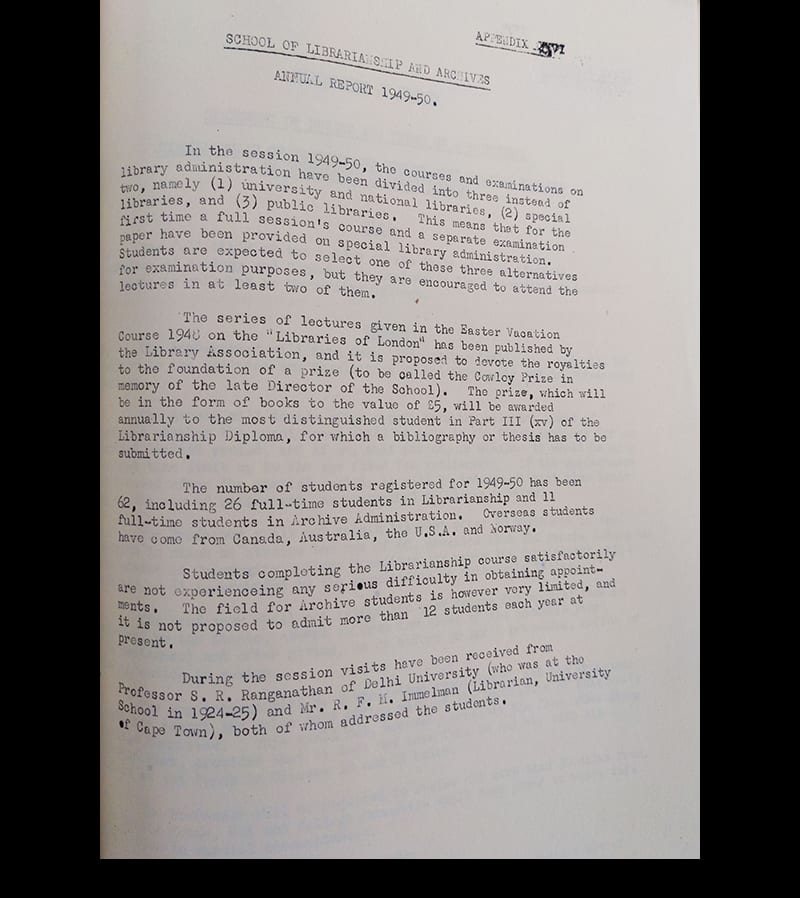

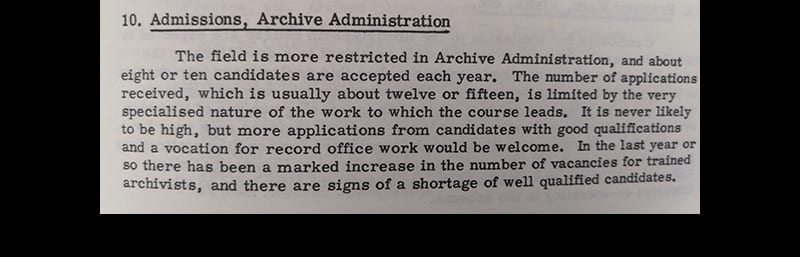

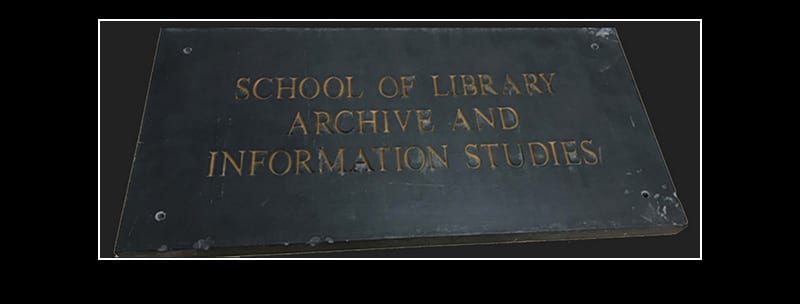

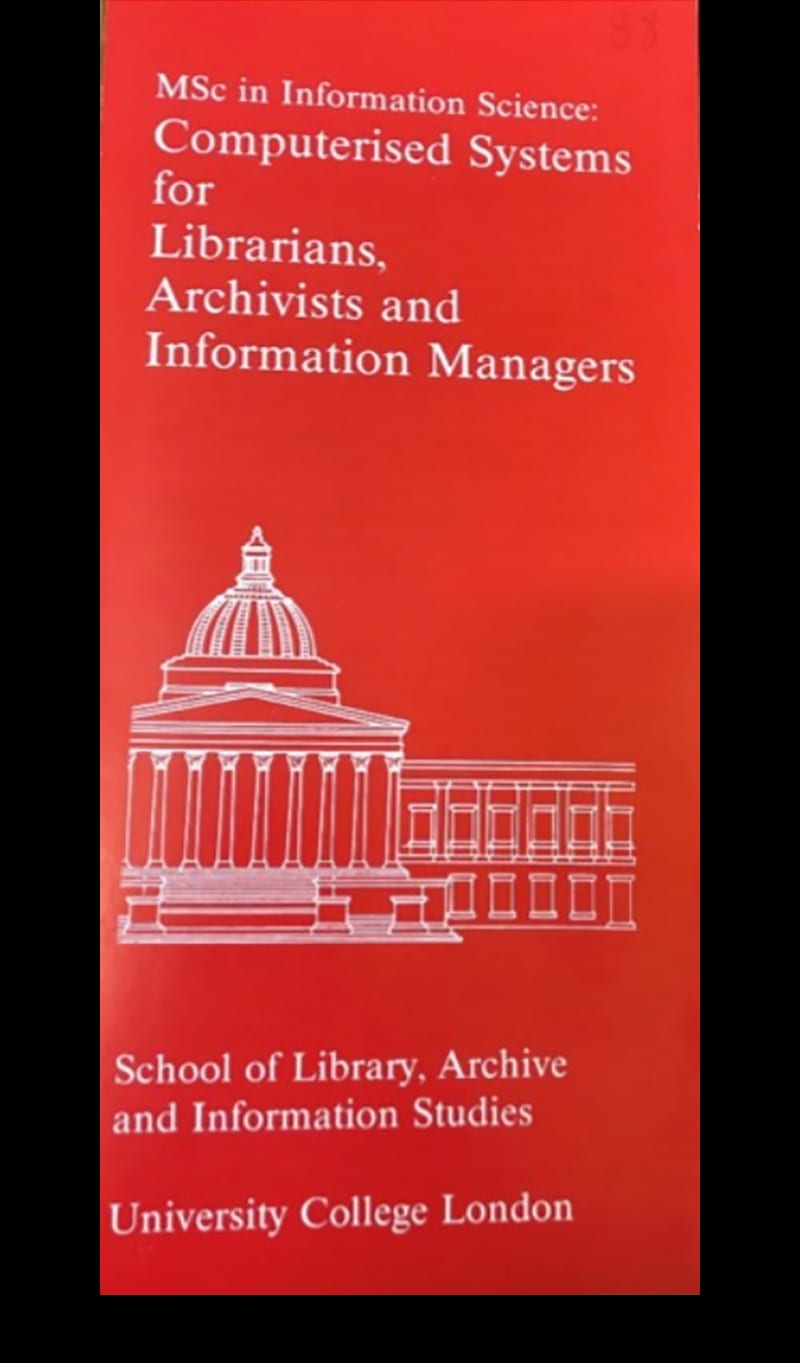

Yes, it was called the School of Library and Archives Studies then in the 1970s. Because originally, it was the School of Librarianship, as you said in 1919. The archives studies were added I think, in 1947, but the archivist will no doubt put that right if I’m wrong, but I think it was 1947. So from then until the time I was there, it was the School of, I think it was, Librarianship and Archive Studies. But then, very shortly after my time as student, it was changed to the School of Library Archive and Information Studies. And that was under the directorship of Brian Vickery. And I don’t think at that time in the 1970s, that we would have had a programme called Archive or called Information Studies. But there was an Information Science route and he was very much an information scientist, so that perhaps seemed appropriate. So it became the School of Library Archive and Information Studies, or SLAIS, and I think that might have been around 1975. Now more recently than that, the name of the then school was changed to the Department of Information Studies, I must say, to much opposition from the staff, certainly on the library and archive side who quite liked the idea of, of it being the School. But I think there was a tendency at UCL to change schools into departments, and there was also a broader tendency in the United Kingdom, for what had been the library schools to call themselves departments of Information Studies, or high schools, so there was some pressure and I’m thinking that would be in around 2008 2009. But a robust defence was put up. And I captured the sign that we had outside the old Henry Morley building, where we had been when I was a student until I think 2011, that said, School of Library, Archives and Information Studies, and I captured it, and put it in my room. And it’s still there. It’s the room that’s now occupied by Charlie Inskip. So if you want a picture of the old sign when it was a school, you can go along there when take one for the exhibition, so it’s had several names over the years.

Sae Matsuno (00:07:47)

Right, it sounds like it’s the name itself shows the history and evolution of the department. So I hope this transformation from the perspective of your professional practice, and later on in our next session. So thank you so much. I’m really excited that you will be sharing your memories and experiences today. As you know, we are dividing our interview into two sessions. So today, I would like to ask you first to talk briefly about your early life. And second, explore the time when you were a librarianship student at UCL. We are also assigned two sets of questions by the current staff. So in the later part of today’s interview, I would like to invite you to define some terms used in these questions, so that we can explore them in more detail during our next session. Is that all right?

Vanda Broughton (00:08:54)

Yes, that’s fine.

Sae Matsuno (00:08:56)

Okay, thank you. So let’s start. Um, can I ask you your year of birth?

Vanda Broughton (00:09:06)

It was 1948.

Sae Matsuno (00:09:09)

Where were you born?

Vanda Broughton (00:09:12)

I was born Colchester. That is c-o-l-c-h-e-s-t-e-r in Essex.

Sae Matsuno (00:09:19)

And where did you grow up?

Vanda Broughton (00:09:21)

That’s where I grew up, and I lived there. And I was going to say until I went to university, but during the time that I was at university, until I got married after university and then I moved to London.

Sae Matsuno (00:09:41)

So that means you never moved to anywhere else, besides the time when you started to go to the university so very much of your early years you were in Colchester.

Vanda Broughton (00:09:57)

Yes. That’s right, I went to school there.

Sae Matsuno (00:09:59)

Okay. Could you tell us briefly about your parents?

Vanda Broughton (00:10:05)

Oh, my parents. I mean this is perhaps not a very happy story. My parents were ultimately divorced. My father was in the building trade. He was a carpenter, and my mother was an accounts clerk, but as both it would have been common for working class people, at the time in the 1940s, they both left school at 14. So they were not, I mean, they had the basic education, but I was the first person in my family to go to university. But my parents were divorced, they separated when I was about 10 and were late to divorce.

Sae Matsuno (00:10:53)

Did you stay with your mother or your father?

Vanda Broughton (00:10:57)

Yes, I stayed with my mother and I had a younger brother. And we lived in the house that we had lived in, we stayed in the family home.

Sae Matsuno (00:11:13)

All right. Could you tell us about your education, which schools and university did you attend before studying at UCL?

Vanda Broughton (00:11:22)

Well, I went to a local Primary School, a Church of England primary school. And then as 11 I passed the 11 Plus; you may know it was the examination for selective education. And I went to a local Grammar School. It’s called the Gilbert school, although it doesn’t exist anymore. So it’s been merged with another school to form a comprehensive school, but I was there until I was nearly 19 and I studied physical sciences for my A Levels, and I loved chemistry, and I loved pure maths, but I did not really like physics, and applied maths. We were taught it in a funny sort of way, I think, by modern standards. And there was an expectation that if you did those sorts of subjects, you would go in for engineering or some sort of applied scientific career, which didn’t really appeal to me. I must say, I was the only girl, I went to a co-educational school, and I was the only girl in my year group reading and studying physical sciences. So I took the entrance examination for Girton College, Cambridge, in natural sciences, but I decided that I would read theology. When I went up, I’d become… I wouldn’t say I was very religious, but I had become very interested in religion in my later teens. So I was accepted by Girton to read theology, and I went up in 1967, and was there until 1970. Quite interestingly, that was in the centenary year for Girton, and it had been, it was… there’s some dispute about this with Royal Holloway College in London, but Girton has always said it was the first place of higher education for women in the United Kingdom, I think in the United Kingdom, but it might just be England. And I think Royal Holloway was founded shortly before that, but not for higher education. It had been a school, so Royal Holloway is slightly older, but Girton I think, was the first place to offer higher education for women, so it was exclusively a women’s college. So we celebrated the 100 years during the time that I was there. But rather interestingly, Cambridge was behind Oxford in this, they did not give degrees to women until 1948, which was the year that I was born. So there’s a kind of strange synergy there. But I graduated in 1970. I had been… I got a First Class Honours at the end of my second year, so I was given an exhibition. So I’m a member of the foundation of the college and I was a college prize-winner, but ultimately I graduated with an Upper Second, I did not get a First. I was vived for a First in my final year, but didn’t get it. I was so terrified in the viva that I think I didn’t do my best there. I was a candidate for the Hebrew prize, but didn’t get that either. So it was kind of lamentable lack of success in life. But no, it was quite as successful final year. But I didn’t do quite as well as I might have done, but the Hebrew prize, which I didn’t get, was a sign of lifelong interest. I’d studied Hebrew as part of my theology degree for three years, and I’ve continued to teach a baby’s Hebrew, not real babies, you know, a beginner’s Hebrew class locally for adults, just in a very informal way, for a number of years now.

Sae Matsuno (00:16:13)

Wow, this chapter, the Girton College, I read a little bit about the college, and yes, it’s one of the pioneer women’s college higher education. So it’s in itself a very, very interesting subject. But could you just quickly touch on that turn from natural sciences to theology? What was the reason? Was there any moment, or you then started to really thought “Oh, I am going to change the subject of my study?”

Vanda Broughton (00:16:50)

I think I really couldn’t see, perhaps because it wasn’t very imaginatively presented to me. I didn’t have a great interest in the sort of scientific career that was suggested to me at school. And I think that’s perhaps because there was a tradition of this engineering sort of study, that didn’t really appeal to me very much. But I was very interested in religion and I think the school felt, because I was the only girl that did physical sciences, they agreed that perhaps I’d been rather pushed in that direction. And that may be it might not have been my strongest suit. So I did the A level divinity. So I had done my A levels in sciences, I also did A level art, and then to fill the year, because in those days, you had to take the Oxbridge entrance exams in the autumn, so I spent half a year doing A level divinity and got an A in that. And I think that possibly demonstrated that my abilities were perhaps equally as good in the humanities, although I’ve always maintained quite a lively interest in the sciences. So some of my, my major interest for me has been classification and indexing information retrieval in religion, but also in subjects like chemistry as well. So it’s been there as a kind of secondary interest.

Sae Matsuno (00:18:54)

So this, these early years, have certainly prepared you to have a very broad range of interests, so to say.

Vanda Broughton (00:19:04)

Yes, I think so. And that’s really useful in my field of library science, and I often say, if people say, Oh, you know a lot about, I don’t know, geology or classics or whatever, no I don’t, but because of the sort of work I do with vocabularies, with terminology, and with designing systems, that you have to get a very quick, superficial knowledge of a subject. So you learn all the terminology, but you don’t necessarily understand the subject. But it has been very useful, particularly to have a good familiarity with scientific subjects. And the thing that I do think, I feel quite strongly, is that the sort of disciplinary approach that you adopt in your school days stays with you, to some extent. So nowadays, although you might call me a humanist, I don’t think in quite the same way, as say the archivists in the department who generally have a background in humanities, probably in history. So often my methodological approach is more scientific. So I tend to be more quantitative and less relativistic. Although I’ve tried to correct that under the influence of the archives staff, so I think it does, it informs your fundamental way of thinking the early type of studies that you do,

Sae Matsuno (00:21:01)

Right, and it’s, it’s really helpful that you are now starting your narrative about your professional career as well, because I wanted to ask, how did you become originally interested in a librarianship career? So we talked about your loving chemistry, for example, and your background in science and in theology? And where does this library and librarianship, library and information studies kicks in?

Vanda Broughton (00:21:35)

Hmm, well, that’s interesting. Some children have just arrived to look at the horses, but they’re, they’re quite big children, so perhaps they won’t shout. To go back to the librarianship, I don’t think I had early on, thought about librarianship as a career. Certainly… not sorry, it’s distracting me a bit now. Sorry, I’ve got a drink here, so I just have a drink.

Vanda Broughton (00:22:19)

That’s all right, a very big group of people have turned up who I’m sure should not be out like this. I’m sure they’re disobeying the rules, but we’ll carry on. I mean I’m not one of the people who said, “Oh, I knew from the age of nine that I wanted to be a librarian”. Because I didn’t, I can remember going into the public library at a very early age. I went, first went to the library when I was five, and I brought home a book about butterflies. And my family laughed at me, because they thought I should have brought home a storybook, which tells you volumes about it. But really, I thought about librarianship seriously, as a career, after going to the Careers Service in Cambridge. They give you a test to indicate what sort of profession your natural abilities or interests incline you towards, and they did suggest librarianship. But at the time, I thought it was really important that I should have some sort of marketable qualification. So I thought I would try accountancy, which is very bizarre in retrospect. So I did actually originally get a job as a trainee accountant, and it became obvious very rapidly that it, I wasn’t going to like it. So I left the job that I had and I got a job in the local library in North London, in Tottenham and I worked at the Central Library in Tottenham at the public library in Tottenham as a library assistant. And occasionally, I went out to various branch libraries in the borough, and I really enjoyed it. And I applied for a place at UCL and got one. So that was my kind of fairly brief library background compared to many students nowadays, who’ve, you know, had several years of volunteering or doing part time work in libraries. I had relatively little experience and, I have to say, probably leading into my experience at Library School, that relatively few people came from a Public Library background. I can only remember one other student, and I’m afraid I can’t now remember her name. But only one other student too had a Public Library background. So most of the people I was with at library school had come from trainee posts in academic libraries.

Sae Matsuno (00:25:25)

Why do you think there were a few public few students with Public Library backgrounds at that time? Can you think of other factors?

Vanda Broughton (00:25:39)

I am not sure, except that, I think, the established routes for going to library school were largely done through the Academic Library Network through the provision of graduate trainee posts. And that was not very well established in the public libraries, so there was a bit of a bifurcation in the profession at the time. Actually, I’m glad you’ve asked this, because I had not been thinking about this, but it’s true that in general, there were relatively few graduates in the public library system. So there tended to be two routes into the profession and people largely in public libraries, who were non-graduates who did the Library Association qualifications, which were usually done through correspondence courses, and they would work for chartered status for associateship of the Library Association, whereas on the other hand, most graduates went to Library Schools, and did a Postgraduate Diploma in Librarianship. We didn’t at that time have the MA that came in shortly after I was in Library School, but I think there were fairly few graduate librarians in the public library system. So they tended to recruit people locally, you know, who lived locally, who’d been to school locally, who hadn’t been to university, who did the professional qualifications through the LA and who did not have degrees. And people who had degrees went to the Library Schools, there were not so very many Library Schools, then most of the bigger ones now were opened just after the war. So UCL had been the only Library School really up until the time of the war. And then places like Sheffield were open, Loughborough were open shortly after that. But the expectation was that we would be subject librarians that’s really what we were trained for, and hence a good degree in the subject. This man opposite here, I’m sorry, I’m just changing the subject is taking photographs of a family of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 people. Shall I call the police? No. Sorry, they’re just distracting me here. But I think I’d finish what I had to say. I’ve forgotten where it started now.

Sae Matsuno (00:28:43)

Sorry for not laughing together, but on the oral history interview, I’m not supposed to laugh.

Vanda Broughton (00:28:50)

I’m really sorry I shouldn’t be changing the subject.

Sae Matsuno (00:28:53)

But I find it so funny, sorry. But so I will allow myself to laugh now.

Vanda Broughton (00:29:00)

Well, I’m sorry for probably spoiling your recording, but really is you know…

Sae Matsuno (00:29:06)

There is a software, sound editing software, so that should be fine.

Sae Matsuno (00:29:12)

Okay, so, let’s move on, then. Well, I think it’s a very, very good moment. I think you are sharing a lot of useful and insightful information of, like, library score students at UCL at the time, were trained with the expectation that they would become subject librarians which is quite interesting, if you consider more various range of librarians that the department in the section of Library and Information Studies are trying to train at the moment.

Vanda Broughton (00:29:57)

Can I say something about that?

Sae Matsuno (00:30:00)

Yes, of course.

Vanda Broughton (00:30:02)

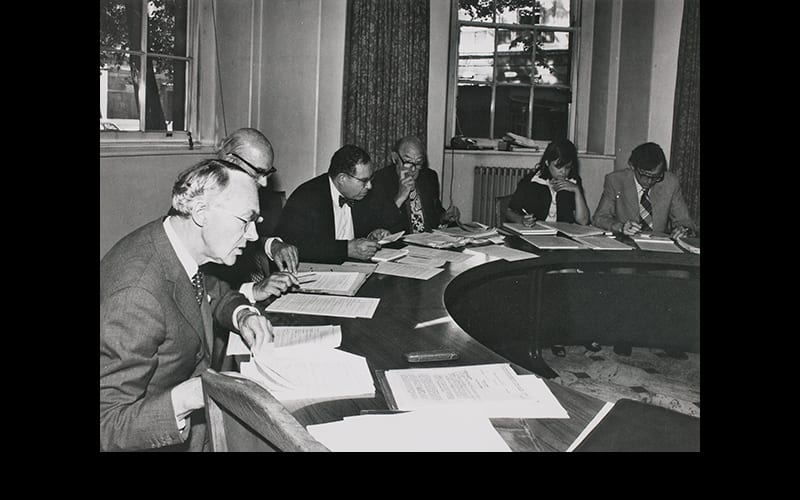

Because when I was at Library School, and I’m sorry if I’m getting ahead of myself, but we were divided into three, cohorts, not cohorts, but three groups. Well, there were some archivists too, but just from the perspective of the librarians, there was a standard librarianship course, which I was on, which consisted of about maybe 30 to 35 students, and we were the ones who were going to be subject librarians, or we were going to manage Special Collections, usually subject special collections of some kind. There was also a teacher librarian’s course. So there were probably fewer people on that, maybe about 12 to 15. And they were people who were qualified teachers, but who were going to run libraries in their schools. So they came to learn librarianship on top of the profession they already had. And we also had a qualification in Information Science. Now, I can’t remember what it was, it may have been a postgraduate diploma, like the librarianship one. But it was run by a man who’s very famous, I mean, long dead, but a man called Bertie Brooks, that’s b-r-double o-k-s, and he’s renowned in the field of Information Science. But these were people who had to have a science degree. So I was a little bit miffed, I was constantly changing my interest and constantly being a little bit miffed about it. But I was not allowed to do any of this stuff, because I did not have a science degree, although I had science A levels. So there was not the phenomenon of this mixing and matching and swapping across and between programmes that is very typical of the department nowadays. So you came in and you did either Librarianship, Information Science, or Teacher Librarianship. And there was really very little contact between any of us, which I think is a shame.

Sae Matsuno (00:32:40)

Yeah, okay. Hmm, well, I think you’ve answered already part of my question, which is good, so we can go back and forth between those different interview topics, so… Well, so let’s spot on… but let’s get the basic information right. In which year did you enrol and graduate from UCL?

Vanda Broughton (00:33:11)

Sorry, I’m just coughing now, haven’t gotten a cough…

Sae Matsuno (00:33:14)

Take your time?

Vanda Broughton (00:33:17)

Hum, yes. So the years I was there 19, September 1971 would have been when I started there as a full time student, and I finished in… Well, I suppose I’m trying to think what we did, because we obviously didn’t do a dissertation, because it wasn’t a Master’s degree. So presumably, we must have finished in June, in 72. So it was possible to do a Master’s degree at UCL at the time, but you have to do another year of study, so it was a separate programme. And I know one or two people who did that, but normally it finished after, you know, nine months as a post graduate Diploma.

Sae Matsuno (00:34:14)

So what sort, just to repeat, what sort of qualification did you obtain when you completed the programme?

Vanda Broughton (00:34:25)

[Coughing] Sorry.

Sae Matsuno (00:34:29)

Shall I pause for a moment?

Vanda Broughton (00:34:32)

No, it’s all right, I just need to drink, I’ve got a drink to one side.

Sae Matsuno (00:34:36)

Okay. Yes. When you are when you are ready, just tell me.

Vanda Broughton (00:34:41)

Yeah, that’s fine. So I am…. So I had a Postgraduate Diploma, which was the normal thing for a graduate librarian then, so nobody would have done an MA unless they did… So an MA would have been a further degree and that would have been typical of all the Library Schools in the country. So Postgraduate Diploma, commonly abbreviated as a Dip Lib, would have been the standard qualification. So that’s what I had. Oh, and I must be boastful again, I did win the medal. So there were various prizes and medals, the MacAlister medal was given to… well… the best performing, the student with the highest grades was given the MacAlister medal. So I was the medal winner in my year, which is very helpful. So I graduated with a distinction in the Diploma.

Sae Matsuno (00:35:52)

Wow. So it’s interesting, because you just told me about the final year at Cambridge, and you worked hard, and you achieved a lot, but sometimes the results were not what you expected to have. So then, at the end of UCL programme, you had this prize. So how did you feel at that time? Do you remember?

Vanda Broughton (00:36:22)

It’s really interesting, because I think, after three years as an undergraduate, I had had enough, and I was very interested in certain areas that I did well in. So the Hebrew was a good thing for me. But I think, particularly as I’d come from a working class family, with no background of scholarship in it, university was a big ask for me. And I reflected afterwards that while I was at university, I learned how to learn. So when I came to UCL, I’d got that, so I didn’t have to start again. So in many respects, the UCL experience was an easier one, you know, I’d finished university, I’d had a year out, I’d come back to it. I was keen for it again. And I think that showed itself really in the results. So yes, I was very pleased with it, you can say that, and it did pave the way for a career in research then.

Sae Matsuno (00:37:48)

Do you remember the curriculum?

Vanda Broughton (00:37:52)

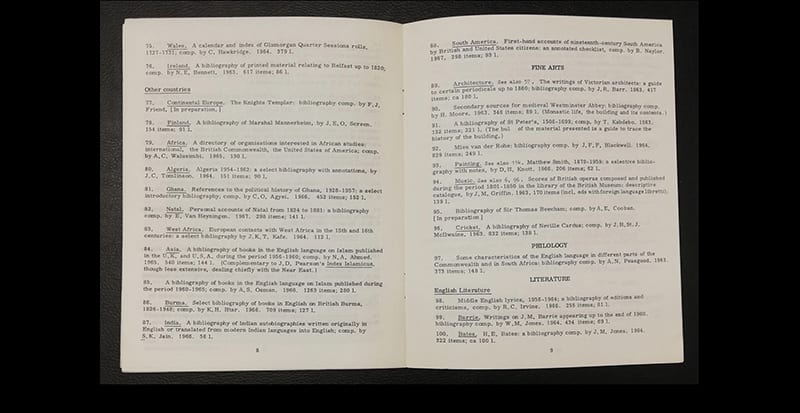

Oh yes, we did… This is really interesting, I think, compared to the modern curriculum, because at the time, made significant thing, and this is the thing that’s been a pattern through my career, was the position of information technology. Because when I was a student, there was very little in the way of information technology. Computers had just started to be used in libraries. I mean, I suppose they were used a bit more in research libraries, but certainly in the public library, and in most sort of undergraduate level libraries, the computer had hardly arrived. I had worked, as I said before, in Tottenham, in London Borough of Haringey, and one of our libraries had a computerised issue system, one out of the whole London Borough. So they recorded the loans and then the system generated a ticket, and you folded that up and you put it, I don’t know whether you remember because you’re very young, but we had things that were called brown tickets, Brown was the inventor of them. They were like little pockets and you had a card in the book, and you put it into your tickets, and then they were filed in the library. So although the computer recorded the transaction, you were still given a little slip of paper, which was put into your ticket. So the use of computers was very rudimentary the. We were given occasional lectures on what people thought computers might be able to do in libraries, but effectively, there was no IT in our course at all, only as a sort of occasional thing. So we had a lot of time to do other things. So we did things like we all did Historical Bibliography, which nowadays, as you know, is an option. So quite a lot of people still do it, but you know, it’s not compulsory. Historical Bibliography was compulsory for all of us. So the option was advanced Historical Bibliography, and I was very crossed again, because I wasn’t allowed to do this advanced Historical Bibliography, because I didn’t have A level left in. Oh nowadays, oh, a sessional lecturer we had, who taught Manuscript Studies said to me, “What can I assume about Latinity” and I went “Nothing”, because nowadays you couldn’t ask people to have any Latin at all to do these subjects. But in the 1970s, you had to have A level Latin to do the advanced course, and I didn’t, I had O level Latin, but I did some Historical Bibliography. We also, on a Friday morning, did bookbinding, which I’m sure many of our current students would love to do. But, you know, there isn’t room in the curriculum for it, but we were taught by Sandy Cockrell, who was the binder at Cambridge University. And he used to come on a Friday and teach us. He bound several really important ancient manuscripts, including the Codex Sinaiticus. So he was a real international expert. So he demonstrated various things to us, but we did a little bit ourselves. We made paper out of wood pulp, we didn’t make any rag paper, but we made some paper and we made a little, you couldn’t call it a book, a little booklet. But we folded the paper, and we sewed it, and we made a proper binding for it, so it wasn’t very thick. So we had lots of leisurely time to do things like that. We also did Cataloguing and Classification and Subject Bibliography throughout the course. So we didn’t have a modular design, as you do nowadays. We did our courses throughout the year. So we did this Cataloguing Classification, which was obviously the thing that I liked the most, and Subject Bibliography because that’s what we were expected to do, and we had to choose two dissimilar subjects to compare the resources for. So it was not dissimilar to the Information Sources course nowadays, which I taught for several years. And I’m trying to think what else we did, we had to do Library Management, during which I didn’t take a single note throughout the whole course because the lecturer, who was a man called Ian Gib, who was the librarian of the National Central Library, which was the foundation of things like documents supply. Now, he didn’t ever say anything that didn’t seem to me completely obvious. So I didn’t write anything down during the Management course. We did some statistics, which again, you know, people wouldn’t have the maths to do it nowadays, but we were required to do it. And then as an option, I did Oriental and African Bibliography, which sounds slightly strange, but it was taught by John Mcllwaine and he was really an Africanist. So if you look him up, you will find that he’s written lots and lots of things about the bibliography of Africa and about African Librarianship. So he knew a lot about Africa, but there were also people doing this option who had studied Arabic, I’d studied Hebrew. There were various people who were interested in South Asia, who had Indian languages. We had one or two overseas students for whom that was a specialism. So that was really quite an unusual and interesting course that I think UCL was the only place ever to offer it. And when John Mcllwaine retired in 2000, it very sadly had to be abandoned. And they said to me, could I do it? Because I’d taken it as a student, and I said, “Well, possibly I could get it up”. I had no great expertise there, but as I was already teaching Classification, and the Advanced Cataloguing course, and Information Sources, I thought it was a bit much to do. So the curriculum was really different. And we took examinations in everything. Written examinations.

Sae Matsuno (00:45:56)

So, how would that examination look like? Is it an essay style?

Vanda Broughton (00:46:09)

Oh, probably, it depends what it was. But probably, you know, a standard, a three-hour written examination with essay type topics. I’m sure we had to do some stuff in the Management examination on Statistics, because I can remember because I could do a Chi-squared test then. But I think generally they were essay type questions, but we did coursework as well. So for each course that we did each sort of the equivalent of each module, we had to do a piece of extended coursework. So it was a combination really, of coursework and examination. I probably did well, because I had good exams.

Sae Matsuno (00:47:05)

All right. So let’s move on to the next question. What sort of relationships did you have with tutors and cares? Do you have any memories of that topic?

Vanda Broughton (00:47:19)

Yes. It’s interesting because it was very much more formal than it is nowadays. So we were always called Mr so and so or Miss such and such, and we would always call the lecturers by their, you know, by their proper titles, and that… I mean, I do, I’ve had some correspondence with John Mcllwaine recently because we’re obviously all concerned about our older colleagues, and I would say, “Dear John” now, but we probably wouldn’t have at the time. And I can remember there was a question, I mean, this is during my employment at UCL, when there was a question of how students should address us, this is probably about 15 years ago. And the Mcllwaines were then in China. That is very interesting, the Mcllwaines … and I probably… hum, we’re nearly out of time now, but I have, at some point, to say quite a lot more about them, but they were in the department for a very, very long time. They went there as quite young lecturers. I think both of them had only had one job on between leaving Library School and coming back on the teaching staff. And they, they were there. They were there, I think, for nearly 40 years. And they taught me and then when I came back to teach, they were at the top of the tree, as it were, she was the Director of the School and he was also very senior. But at some point, about 15 years ago, when some students asked about how they should address us, and I said, “Oh, I don’t mind, you know, they could call me whatever they liked”. My colleague said, “Yes, you know, whatever they feel most comfortable with”, because we know that some overseas students don’t like to be too familiar with staff, some home students as well. And Ia Mcllwaine said, “And they can call me Professor Mcllwaine”. So even quite recently, she died last year, sadly, but certainly there wouldn’t have been any question about it. When I was a student is that they were you know, Dr Mcllwaine, or, you know, Miss Pickett taught me cataloguing. But the Mcllwaine, in particular, they ran the MA, what was then the Diploma course between them, and they were immensely protective of their students. They were the people who really dealt with students on a day-to-day basis, you know, they managed the course, they did the interviewing, and admissions and so on. And we were… I was trying to remember whether it was all of us, or whether it was just the people who were on the Oriental and African Bibliography course. But I could remember going to their home, their flat in, East Finchley, North London. So they entertained us, and they sort of looked out for us, but they were still fairly formal in their dealings with us, but that was perhaps more typical of the 1970s. So it wasn’t all kind of maytee as frankly it is nowadays, but I think they were equally concerned with our pastoral care and with our welfare, it’s just that they didn’t express it so informally.

Sae Matsuno (00:51:12)

And also in that, some of the faculty members and educators staying at UCL for many, many years, they were also able to develop this long-term mentorship with students. Do you think that way as well?

Vanda Broughton (00:51:33)

Oh, yes. And I mean, I think you have to, again, mention the Mcllwaine in particular. They were long standing members of IFLA, you know, the International Federation of Library Associations. They went every year to the big international conference, they sat on committees, and so on, at IFLA. And as a consequence, we had a lot of Commonwealth students come to the, I call it a School because it was a School then. So a lot of people, particularly from Africa and Asia, came to the school because they had met the Mcllwaine at conferences. And this went on for years, and years, and years, even after they’d retired. And in fact, I was joking with John online because I had to write various obituaries for Aye when she died last year and one of the things I mentioned was the people who would just turn up in the in the School, probably on a Friday afternoon, and they would say “Is Mr. Mcllwaine here?” and we would think, probably not on a Friday afternoon, and they would go, I’ve just come from, you know, Uganda or, or, you know, Sri Lanka, or somewhere like that. And there was an expectation that they would be sitting there ready to receive these students.

And of course, very often they were, they did, and they would be invited back home. But they in particular formed relationships with students at an international level that lasted decades. And then there’s me, of course, because I went… hmm, came as a student and went away, but you know, that relationship was maintained, and then when there was a vacancy, they thought, “Oh, you know, we’ll see if she’s interested in the job”. And because I’d worked in the same sort of area, as Ia Mcllwaine, and certainly not so much now, but at one stage, a fair number of the staff were graduates of the school, who came back later to teach. I don’t think that was necessarily a sort of nepotism. I think it’s just that we had very good quality students who had a long-term commitment to the school. We’re going to run out of time in a minute, aren’t we?

Sae Matsuno (00:54:24)

Oh, no, it’s fine. My son comes back at 5pm. So as long as you have time, that’s fine.

Vanda Broughton (00:54:34)

Yes, yes. Yes, I’m okay at the minute.

Sae Matsuno (00:54:39)

Yes, so there was certainly a sense of community when you are student at UCL. And that sense probably just grew as time went.

Vanda Broughton (00:54:53)

I think so. I mean that might be a thing, particularly for me, because I have quite a strong sense of the academic community, particularly the research community.

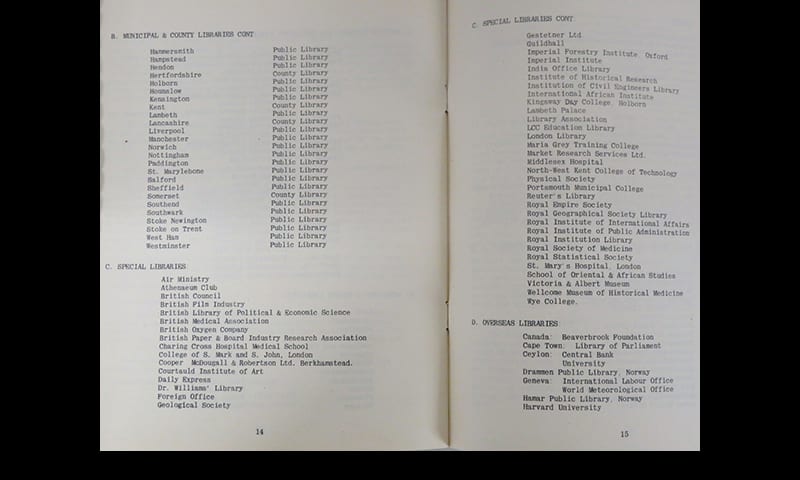

And it’s the thing that I find important, you know, that I, I know somebody who knew Ranganathan, and, you know, is this sort of thing that I’m handing on the baton as it were. But I now have a student some years ago, who’d gone out on a placement during the long vacation, and she came back, and he said to me, “Oh, Henry Morley cast a long shadow”. And what she meant was, I mean, she referred to the department as Henry Morley, because we were in the Henry Morley building.

But she meant that the department had an influence on an awful lot of places. And I think that’s the case. I mean I haven’t done admissions for a couple of years now, that is often the case that somebody comes, is interviewed for a place, and there is some institution, you know, some parts of the University of London, or somewhere like Lambeth Palace or, I don’t know, the British Library. And they will say, “Oh, Simon sends their regards or sometimes sends their love”, and you go, “Oh, I didn’t know so and so was there”. So it’s a way of tracking where students have gone. But what we do find is that there are an awful lot of ex UCL students in an awful lot of libraries, and I would say, and particularly in the London area, because that’s where the concentration of libraries are. But they obviously think about UCL, they recommend their staff to go to UCL, they’ve been immensely helpful in coming in to speak, you know, to give lectures sometimes to teach more formally, to offer placements to students, or to host visits and so on. So, there’s, I mean, we often say, that part of the characteristics of the UCL department is this interaction with the profession, these very close ties with the profession. But actually, if you analyse it, is very often an interaction with ex UCL students. So there’s a very powerful network there. I mean, it’s, it’s a great marketing ploy that I think, you know, perhaps we don’t emphasize enough, but there does seem to be quite powerful loyalty of students, they obviously feel a strength in that relationship. It’s all quite interesting because in recent years, we’ve… the college, the UCL has tried to discourage us from interviewing students for places, you know, because they don’t interview undergraduates so much. Now, they make the decision based on a paper application. But we’ve always been very insistent, because we, we like to see our students and also an application to library school is quite complex, because you’re not looking just at academic qualifications as you are with undergraduates. But you’re looking at their practical experience that their knowledge of libraries, things like volunteering, and other activities that they’ve been involved in. So we think it’s really important that we do interviewing, but you know, we mentioned it to one or two students, and they said, “Oh, but that’s awful to think that you wouldn’t interview”, because it’s actually their first contact with the department and they really value that, that they come into the department just as an applicant for a place, but they meet staff in the department, and they form that relationship then. So I think that the relationship between the department, between students and the profession as a whole is a really complex and really important thing. I would be interested to know whether other departments have this, but I doubt it. People are very loyal to Sheffield. Sheffield is a really good school, I know, but I imagine of the people that go to Sheffield, and hardly any will stay in Yorkshire, whereas the huge majority of students who come to us do stay in the London area, or they’re part of a network that involves London. So yes, I think it’s a really, really important thing.

Sae Matsuno (01:00:36)

Okay, hum, so the next question will really relate to your skills in research. So it’s been really interesting that you’re mentioning the really close relationships built within the UCL Library and Information Studies community, and in what ways was teaching at UCL helpful and stimulating for you in terms of developing your research skills?

Vanda Broughton (01:01:16)

That’s an interesting question. I think, first of all, in a very general sense, there was a strong emphasis on academic excellence. So, we were a relatively small cohort, we were generally very well qualified. I have to say, unlike today, nearly everybody was funded. So we all got bursaries, but from the Department for Education I think it was then, that you obviously had to have a certain academic level to qualify for that.

So there was quite a strong sense to, that Library Science was an academic discipline. I’m sorry, because this is another bee in my bonnet. Because I think possibly in the non-university schools, mind you there weren’t non-university schools, but the non-graduate route it was taught more as a vocational thing. So you were taught what you needed to know for practice, whereas I think in the university schools, there was more of feeling that librarianship was closely related to scholarship, and because we were expected to be subject librarians, we, it was anticipated that we would have good knowledge of an academic discipline that we would be well informed. Quite a lot of people, even nowadays, come into the department and they already have higher degrees. So they have a Master’s or occasionally a doctorate in an academic subject, and more often than not, it will be the case that they hope to practice as a librarian in that area. So there’s this fairly strong association of librarianship with academic study, with research. And I think we were taught things with that in mind. So there was always quite a lot of background reading. There was an awareness, or we were made aware of research in our topics, of current development, and there was quite a strong intellectual element to the things we were taught. So I loved classification, from the beginning, I think you might find that very many people don’t love classification, and it’s always been history of it that it’s a difficult thing to do. And I didn’t find it so, but I did find it absolutely fascinating, because it seemed to me that it did have some real intellectual meat in it, it did, it posed questions of philosophy of critical thinking, of analysis. Sorry, I’ve just heard a little jingle, I don’t know whether that’s something landing in my email, or something to do with the Zoom… hum might be the email. So I think there was that sort of culture in the department, but certainly, from the perspective of the classification, it was taught in a fairly rigorous way, which appeal to me greatly, sometimes didn’t appeal to other people. But, hum, I think, in all the, it’s hard not to call them modules, in all the courses, there would have been the same approach that was not a matter of just of learning the basics, but it was of learning the demands of the discipline of being well read, of being well informed, of being aware of research in your area, because of course, the expectation was that you would be going back into academia, to support scholars in their study and research.

Sae Matsuno (01:06:10)

And you did and stay in research area, and you chose it as your career, I suppose.

Vanda Broughton (01:06:20)

Well, I’ve had quite a varied career, but yes, that was my first thing. So what I did was really not very typical, but it so happened, that it was then the Polytechnic of North London library school, which was at the time, was the biggest library school in the country, and they had an opening for a Research Fellow to go and work with Jack Mills, on the revision of Bliss’s Bibliographic Classification. And of course, you know, the job description could have been written for me. I mean it was absolutely what I wanted to do. I was really well equipped for it. So it was a no brainer, really, as this eight-hour day is, is that I applied for the job, I went to see Jack Mills, and I was appointed. But of course, not very many people would have gone to a job like that. So it was an unusual sort of job. But I did stay there for 18 years until the money ran out. So this was the only thing if I can, I’m sorry, because I’m jumping about a bit all over the place. But this was the only… sorry?

Sae Matsuno (01:07:57)

We are we are on the track, so that’s fine. And so that’s the first job you’ve got at the Polytechnic of North London. Did I say it correctly?

Vanda Broughton (01:08:09)

Yes, that’s right.

Sae Matsuno (01:08:10)

Okay. So in what ways… So that’s the last question I have for your student time at UCL. In what ways did teaching at UCL prepare you to start with your career in Library and Information Studies? What was that you gained from your education at UCL?

Vanda Broughton (01:08:38)

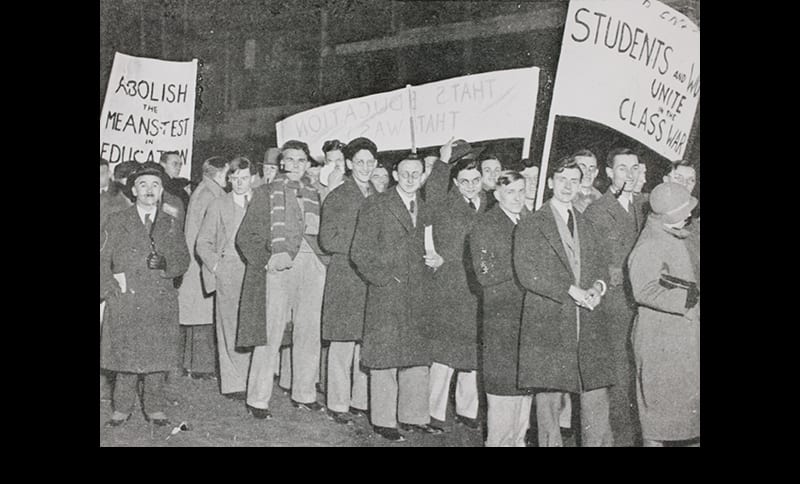

Well, I suppose I just had a very thorough grounding in classification, because that was what I was going to do. As I say, we were made aware of the development of the field of what was going on, of the sort of theory and philosophy of it, which was clearly going to be really important for me, because I was going to be involved in the design of systems. Well, design of classification schemes, so the fact that I had had that good grounding was really important. And the enthusiasm really, that had been engendered in me, for the subject. And I guess that that would be true. I’m trying to think how it might have been if I’d gone to be a subject librarian somewhere, but I think we, I mean, we also had a real thorough education in things like the subject bibliography and information sources. So again, if you were going into a library, and your role would be as subject support, so you might be a subject librarian or a reference librarian or a sort of inquiries person, you would have been really well equipped to deal with most of what came at you. So although I went to an odd sort of job, I did think that I was well equipped for it, and I think we would have been for other things. Incidentally, I did… I was going to say, you know, it was the only sort of political impact on me, but it was the beginning of Margaret Thatcher’s government, around 1980, because of cutbacks, sort of monetarism, and so on, and much less money put into the public sector, it became harder and harder to get money for research. So I had been employed for 18 years, I’d never had any sort of permanent job at North London. We were always working with grants on research contracts, so you’d have money for two years, and then you think, where’s the next money coming from? Unless we got you know towards 1990, it got more and more difficult to find that money. We’d have, you know, 10 years of Tory misrule, you know, don’t quote me on that, because that’s just a joke, really. So, really, at that point, I went back into practice, and I was a sort of subject librarian in a mixed economy college here locally in Suffolk, but I could remember how useful that early training in Subject Bibliography had been. I was the only person on the staff that could answer a legal inquiry in that library. It was a big Community College and the second biggest college in the country. And I can remember how I referred back to the education that I had at UCL nearly 20 years before. Of course, you have to say it was a bit before the great burgeoning of digital resources. But even so, you know, the kind of way of thinking, the familiarity with subjects, the familiarity with dealing with complex inquiries was certainly, you know, an inheritance from UCL.

Sae Matsuno (01:13:03)

All right. Oh, yes. And I think I’m going to move on to the next topic. This is the last topic about today’s interview. And so, in our second session planned next week, we will explore your professional practice more extensively.

Sae Matsuno (00:00:02)

14th of April 2020, my name is Sae Matsuno, and this is the second session at my interview with UCL Emeritus Professor Vanda Broughton. Thank you Vanda for joining me again. So last week, we talked mainly about your librarianship studies at UCL. So today we will focus on your career. Is that okay?

Vanda Broughton (00:00:33)

That’s absolutely fine.

Sae Matsuno (00:00:35)

Okay, so my first question, what are your main research interests and areas of teaching?

Vanda Broughton (00:00:44)

Right? Well, that’s very easy to answer. Sorry, going to cough, now. Obviously, the main area that I teach and research in is Classification, and Indexing. Sorry, a herd of people have just turned up to look at the horses, so I hope you I hope that’s not interfering with what I’m saying. It’s probably more of a nuisance for me than it is for you. But my main interests are classification and indexing. But I’ve also taught at the department in UCL Information Sources, as well. I think it’s still called that in the programme. Hmm, but it’s quite a diverse subject that’s been taught in different ways. So when I was a student, we were taught it very much as Subject Bibliography. When I taught it, I taught it more as Reference Sources or Sources of Information in different formats in different subjects. And now I think it’s taught with a more of a lean towards literacy, Information Literacy. But that although I greatly enjoyed teaching that, and actually, I really drew on my practical experience as a practising librarian to do that, the Classification is the main thing. So I’ve taught that, again, this is slightly different now to what it was when I was teaching it, but we had both a core Cataloguing and Classification module, and an Advanced Optional Cataloguing and Classification module, of which I taught the Classification element. I think that currently Classification is a more minor part of the Cataloguing module, and I teach an option called Knowledge Organisation, which is probably what I like to call my field, rather than Classification, and that doesn’t have any cataloguing in it. So it’s rather than a different setup, now. But that classification has been my main research area, as well. So when I was a student at UCL, my first job, or after I was a student, I should say, my first job was to work on the revision of Bliss’s Bibliographic Classification, which was a large scale project going on at the Polytechnic of North London Library School, which was to revise Bliss’s Classification, which was generally regarded as the most scholarly and the best structured scheme, and to incorporate into it, all of the classification theory that had been developed in recent years. I was going to save the last 50 years, now, of course, we say the last 50 years, but at the time, we were probably quite a lot nearer to the work that had been done by the classification research group. So that’s the basis of my research work. And there’s been some spin offs from that.

Sae Matsuno (00:04:38)

Sure, could you, well you talked about the courses you have taught at UCL. Could you briefly summarise the roles you have had at UCL for the past 23 years?

Vanda Broughton (00:04:54)

Oh, goodness. Well, I suppose… Originally, in 1997, as a researcher, and that was to work on the UDC, the Universal Decimal Classification. But I came onto the staff more formally as a lecturer in 1999. When I came out of my probationary period, I was after that the Departmental Tutor, which nowadays is called the Director of Studies, and again, there’s a bit of a shift in the roles and responsibilities there. But that was basically to deal with things like discipline, and the curriculum and student support for the taught Masters. From 2008, I was also the Programme Director for the Masters in Library and Information Studies, which I did for a number of years.

In 2011, I started acting as the Graduate Research tutor. So I had responsibility for the doctoral students. This was partly to cover staff absence, but it carried on for a while after that, that was a job I did particularly like. Towards the end of that period I stopped being the Programme Director, and I had stopped being the Departmental Tutor some time before that, to say, is that too confusing?

Sae Matsuno (00:06:54)

No, no, no. So it means that for many years, you were in the position to have all the departmental development, and also, you were involved in all levels, the development of all levels of studies done, conducted by students. Is that correct?

Vanda Broughton (00:07:20)

Yes, that’s right. I think, particularly the Programme Directors role was probably more all embracing than it is at the moment, I think there’s been a move recently to try and delegate some of the parts of the Programme Directors role. So let’s say things like admissions, or work placements and so on, are done by different individuals on the team. But when I was the Programme Director, certainly when I started as the Programme Director, the Programme Director did all of that. So you were the person best placed to have an idea of the programme overall, although, of course, obviously, we did involve other people in these various activities, but yes, so I’ve dealt with both the taught Masters and the research students in a sort of administrative and pastoral capacity as well.

Sae Matsuno (00:08:25)

Okay, right. Thank you. So my next three questions are based on the critical areas of inquiry assigned by the current staff members. And each question is divided into three sub questions, which will help us explore your experience with a focus on your work at UCL, but as necessary, please reflect on your work before joining UCL. So my first question is, first, “What have been the major changes in the economy and technology over the course of your career?” That’s the first sub question and I will move on to the second now, “How did they affect your field?” And third, “What challenges and opportunities did these changes bring to your research and teaching at UCL?” So first, “The changes in economy and technology and the impact of it on your field in general”, and then third, so “What were the challenges and opportunities for your work at UCL?”

Vanda Broughton (00:09:45)

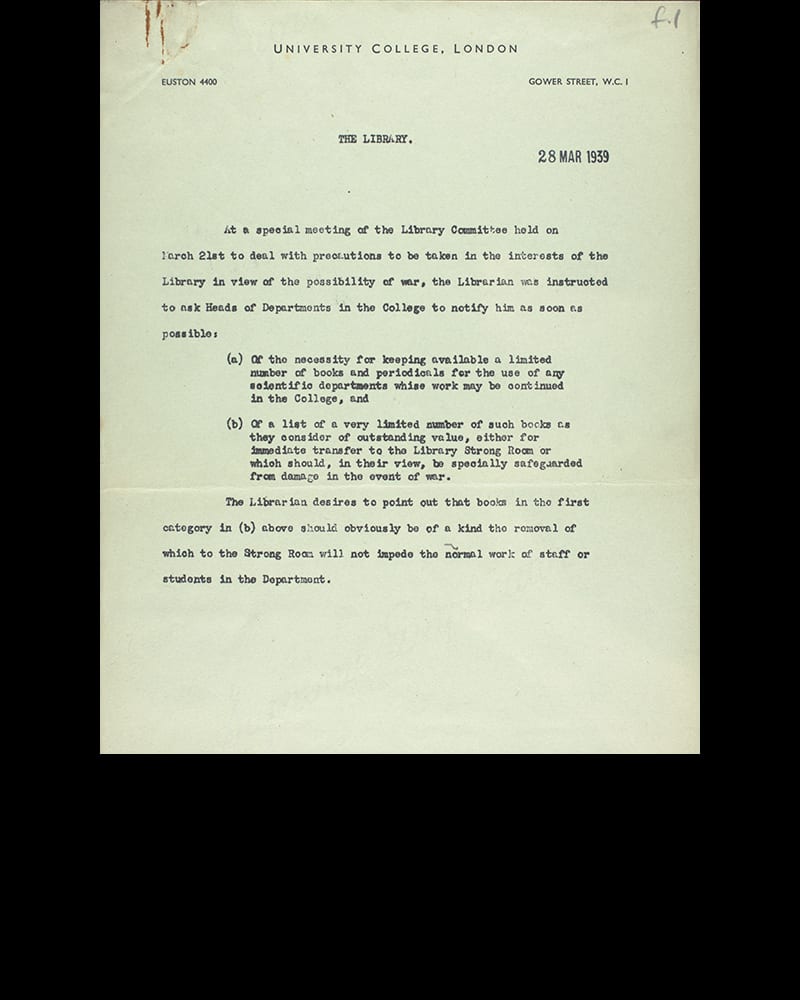

Right, so undoubtedly, the hugest change, and I’m sure anybody in any area will have said the same thing, will be the arrival of automation in a major way, particularly the World Wide Web and all the implications that it has. And these are both technical and economic, certainly as far as they affect the cataloguing and classification area. Now, this is not to say that mechanisation arrived, sort of during my career, because probably when I started, there was a certain element of mechanisation in libraries, but it was very much internal and managed. Say we would have seen the first computerised catalogues and databases and things like that when I began practising in the 1970s. They would have been coming into years. But there’s a big difference between managed automation of information management, and the sort of open sea of the Internet as it were. So sorry, I’m trying to formulate my thoughts here. Hmm, certainly, when I began as a professional, most classification, most indexing would have been done by people in-house, and although you might have had computerised catalogue and used databases, and so on, they were very much local to the situation. So there would have been a lot of in-house work in classification and indexing and database construction. We then moved to a stage where there were more publicly available things and we would buy in databases. And that made a huge difference to the way people managed things. But then, of course, what happened was the World Wide Web, and… sorry, I just need to drink. So there was a big shift that actually happened while I was in practice, and it happened over a period of probably less than 10 years, is that we went from print based materials to sort of internally managed electronic resources. So we have things like CD ROMs, and databases, and then we moved on to the World Wide Web. So there was a change, really. First of all, in the skills that end users needed. So there was a big upsurge in the need for things like users education, what today we would call information literacy. So that kind of ties in with my information sources responsibility. So there was a big change there. But there was also a huge change in what we might broadly describe as cataloguing. Because when I was a student, it was assumed that anybody working in a library, particularly in an academic or research library, would do their own cataloguing classification. And you would probably build your own classification scheme. Now nowadays, we’re light years from that, because with the advent of the World Wide Web, and the fact that we could now see everybody’s catalogue online, there was no need for… Well, there was a need, but there was generally not perceived to be such a need, for people to create their own catalogue records. So the argument was, if people at the British Library or the Library of Congress are creating catalogue records, then we should just copy those records or import them or borrow them or make use of them in some way. Now, nowadays, that’s gone to sort of right to the end of the scale, where many libraries certainly in the UK, in academia, don’t do any cataloguing or classification at all. They just buy in records, or they outsource the work. And that may come down to completely outsourcing the whole process, so nothing happens at all. Now, if I can just carry on this theme, there are considerable consequences for that, because it means that you can’t use a local system, if you want to do that. You can’t use a classification scheme that is not one of the main ones, i.e. Dewey or the Library of Congress Classification. Because if you’re importing records, or if you’re outsourcing your cataloguing process, then the records you will get, will have Dewey or Library of Congress numbers on them. So as a consequence, we saw a great move away from what we might call, not minor classifications, but sort of other than the top two. So many libraries changed from classification schemes like UDC, or in my case Bliss’s scheme, which was used in about 60 to 70 libraries in this country, when I began working on it, and nearly everybody who used it has now changed to either Dewey or Library of Congress. So there’s been a big drop in the number of perhaps what we might say, better classifications, and there’s been a big change in the way that libraries are organised because they’re now all organised, according to Dewey, or Library of Congress. And at the time, when these major changes were going on, there were lots and lots of complaints from practising librarians, particularly those who had subject’s special collections, because their libraries were no longer set up in a way that particularly suited their users. So we’ve had a great loss in the customization of library organisation to suit the using community. I’m sorry I’m going to stop there, because I just go on, on, and on about this.

[Giggling]

Sae Matsuno (00:17:21)

And so there’s also shift in the way investments are made.

Vanda Broughton (00:17:27)

Yes, because the major driver here is financial. So very few, even… the very largest libraries do, but many medium-sized academic libraries, many University Libraries, will no longer have a cataloguing department, well they do have the cataloguing department, but basically, it’s just to deal with incoming data from outsourcing, and there are all sorts of consequences of that, not least the loss of expertise. Now often what happens in these situations is that the cataloguers are dispensed with, but subject librarians, this happens at UCL that subject librarians continue to do the subject work or the classification. But even that has to some extent changed with the rise and rise of Library of Congress subject headings. So that’s another factor in the mix, is that, I think there are only about two academic libraries in this country that don’t use Library of Congress subject headings. So there’s been a shift away from the physical organisation of the collection, the use of a classification for browsing purposes, to the use of Library of Congress subject headings as a subject search tool. So, Cutter would have said this, the burden of retrieval falls on the subject headings. So they do the work for any user wanting to find out what resources the library has on a particular subject. And that, of course, is very much in line with trends in subject search and retrieval on the Internet, because that word base searching is very much the style of a big search engine. So it’s what users become use to. And I think there’s also a trend away from having to learn the systems that are used in the library. So the old user education is rather differently focused, because users nowadays will expect searching on the library catalogue or over a Library’s holdings to be more intuitive and more light Internet searching, so they’re not very tolerant of anything that requires much in the way of familiarity with local systems.

Sae Matsuno (00:20:36)

So that means that users are gaining information in a more manual style way than really thinking about the mechanism and how it works and what it means.

Vanda Broughton (00:20:53)

That’s right, you see very much. Well, when I was in practice, which I know is, you know, about 25 years ago now, but a lot of the user education we did was to show people how to use systems and how to search effectively. Now, there is still an element of that, and I think there is some concern that many digital resources do require quite a high level of information literacy to use them, and people don’t always have that. So there is what we might call a digital divide in terms of people’s literacy, as well as the normal sort of digital divide between the haves and have nots, as it were. But I think on the whole, the expectation nowadays, is that users will expect searching retrieval to be a very easy and intuitive process.

Sae Matsuno (00:21:58)

So with all these changes, what have been the challenges and opportunities, particularly in what you are research and teaching at UCL?

Vanda Broughton (00:22:12)

Well, that’s interesting, if I can talk about the research first. It obviously meant for us, I mean, particularly in the Bliss Classification Association, that we no longer had any expectation that any new libraries would come along and use Bliss, because the ones that were using it, even though it was generally regarded as the best classification scheme, they were all switching to either Dewey or Library of Congress, because that had to fall in with their arrangements for outsourcing the cataloguing. So it was down to us to promote the scheme in a rather different way and to show its appropriateness to a new digital environment. So a lot of the work that we’ve done recently, is aimed at showing how… we probably talk more about the Bliss vocabularies now, rather than the classification scheme, although some people still value the structural elements of it. We see the future of it as being largely an open source, the vocabulary source for people who are developing search tools, either for specific contacts or more generally, for the web, because one of the factors in web retrieval is that very many people who are good at designing systems are not good at designing vocabularies, and so they know how to make the search mechanism work, but they don’t understand the conceptual side, how subjects are structured, how concepts are related to each other, how you achieve things like navigation, search, formulation, and modification, and so on. So we’re looking nowadays at slightly different applications of the classification scheme in terms of its role as a source of vocabulary. There’s also quite a lot of interest in facet analysis. Generally, facet analysis is probably the dominant… hmm, I’m quoting Birger Hiørland from Copenhagen, now, the dominant method of the 20th century and you’ll know, it was devised by Ranganathan, who was a student in the School in the 1920s, so that’s a very famous link for us with classification, but he is generally credited with devising faster classification, although it’s clear there were, throughout the earlier 20th century, there were lots of systems and models that were moving towards that sort of structure. But faster classification is the dominant theory, the dominant methodology behind the revision of Bliss. And, of course, it’s particularly appropriate to online retrieval because of the way that faceted classification is structured. So there’s quite a lot of interest in faceted classification among web designers, and information architects, computer scientists, and so on. So there’s quite a bit of work, I mean, not things that I’ve necessarily done, but things that other people are doing, looking at these sorts of structures, in developing tools for search and retrieval. So that’s sort of, I won’t say its peripheral, it’s sitting alongside the sort of conceptual work that I do, is this technical work that makes use of that. So you know, there are new fields to plough, as it were. So, the theory and philosophy of knowledge organisation of structured vocabularies is still hugely important in terms of information organisation, management, indexing and retrieval. It’s just that it now works in a different way to how it did when we were largely dealing with large physical collections in a local environment.

Vanda Broughton (00:27:16)

Now, if I can say something about teaching, when I was taught classification, we were just taught the major schemes, we were taught the theory behind them, but most of our classification course would have been, how to use these things. And it’s really interesting, because if you look at textbooks, written during the latter part of the 20th century, that is largely what they’re about, “What are the rules for this scheme?” “How do we use it?” “What are the advantages and disadvantages?” Well obviously, nowadays one has to be a bit broader than that. So nowadays, when I’m teaching, I need to include things like the digital environment, different sorts of tools, things like thesauri, and taxonomies, I only dip a toe really into ontologies. But to look at the relationship, particularly the similarities between the classification scheme and these other things, so that students are aware that when they do classification, that they’re not just talking about putting books on shelves in the library, but they’re talking about a structured approach to managing information in a digital environment, and that might be, you know, in a corporate situation, as well as in an academic one. And, of course, apart from anything else, we now have to teach these digital versions, because we will no longer, probably from now, or from the next edition, not have print copies of Library of Congress, or of Dewey. So the old print classification schemes that were so nice, because you could sit with them open on the desk, and if you did something different in your library, you could make some nice notes and say here, you know, we understand this class to be so and so and so, nowadays, you’re using a common online tool, either Classification Web, or Web Dewey and the way you use it, particularly Web Dewey is very different, and I think, if I can have a little grumble about it, that Web Dewey is not very easy for beginner classifiers. But then, in case I get sued by the Dewey Corporation, I better be quiet about it. But there’s a big difference in the way that you access these schemes now and a different skill sets that students need to be taught in order to use them.

Sae Matsuno (00:30:23)

Okay, it’s really interesting to hear that knowledge organisation, including classification, has been taught in a way that students can understand the wider implications of the subject area in society. And so I’m moving, I’m moving on to the next question. So this is, again, a set of three sub questions. So I would say first, second, and third. So first, “How has British society changed since 1970s in its way of looking at and dealing with bias?” Second, “How has that influenced knowledge organisation, research and education? And third, “What have been the implications of these changes for your work at UCL and beyond?”

Vanda Broughton (00:31:27)

Right, so it’s a big ask to say how society changes.

[Giggles]

Sae Matsuno (00:31:34)

If you could share your views, yes, then that was great.

Vanda Broughton (00:31:38)

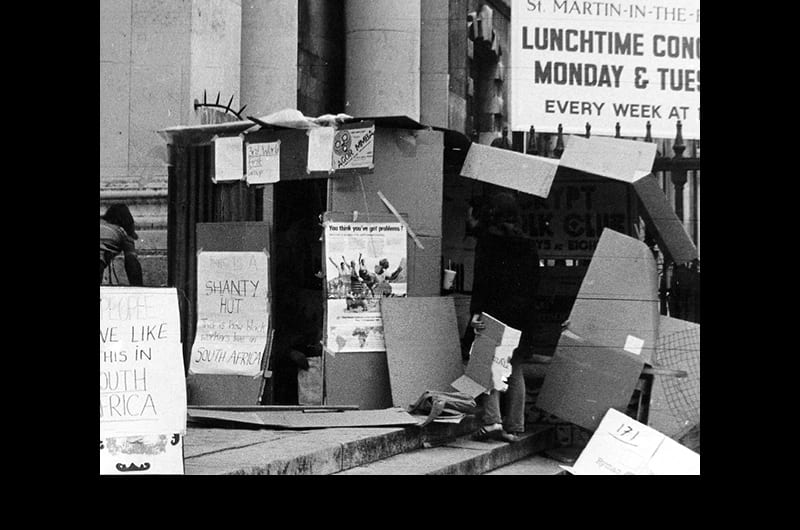

But I think you know, in terms of minority groups, probably, in the 1970s minority groups were not so vocal. Now that sounds critical, and I should perhaps, say it differently. There were not the assumptions… there was no Equal Opportunities Act. I think at the time, the Equal Opportunities Act, I think probably came in around the 60s, or 70s. Then we were primarily concerned about equal opportunities for women. And it was really much later that people began to look at equal opportunities for people who were a minority in other ways. So I suppose the next thing would be in terms of racial or ethnic equality, and probably much more recently, in terms of disability. So things like the special educational needs and Disabilities Act and things that really impinged on universities and our libraries is actually really quite a recent thing, possibly only about 10 to 15 years ago. So minority groups have all sorts now have much more of a voice than they did 50 years ago. I mean, it would have been, this is a hard thing to say, really, but there used to be a kind of vaguely joking thing that we interviewed everybody at UCL, because if anybody with a disability came for an interview, they could see how difficult life was going to be for them. And they might be discouraged from applying. Now, you know, that wasn’t official policy, but that was the kind of the culture of the place. And I can remember going to meetings in the wider College, where people in Science Department said, Well, we can’t have people with disabilities here, they’d be too much of a liability. So there’s been a really big change in the idea of openness and fairness, and access and equality for all that really, really was not there 50 years ago, so people have more of a voice. And we can actually see that. I’ve written a bit about this recently. So there’s more in the literature, certainly in the knowledge organisation literature, about the needs of minority groups of all kinds. And I would say that probably that sequence of sort of gender equality, then ethnic equality, then probably equality in terms of sexual orientation and more recently disability equality. So there’s a literature on all of these topics in terms of how these groups are served, and how they’re represented in the big classification schemes and in things like Library of Congress subject headings. And of course, that’s really significant. First of all, because it upsets people, you know, it offends people, if you use the wrong sort of language, or you put things together in a wrong way. So there’s a lot of personal hurt caused here. But also, there’s a problem with retrieval. Because if you don’t describe minority groups, or the resources relating to them in the right way, then nobody’s going to find them, nobody’s going to discover them. If you use antiquated language, if you don’t use the terms that people use themselves, they’re not going to search in the right way, and they’re not going to find things. So there’s really two things: there’s that kind of social cultural dimension to it, but there’s also a sort of technical and practical dimension of people not being able to find things. Now, very often, in the past people couldn’t find things, because they were not named. So if you belong to a particular ethnic group, say, and that’s not represented in the Library of Congress subject headings, then you’re never going to know whether there’s anything appropriate to your interests or about your particular community, because that never gets recorded in any way. And I’m thinking here, really, particularly in North America, there was quite a bit of literature on what’s now called First Nations, the sort of original American and Canadian Indians, and they were, they were simply not included in the vocabulary, so that material never, never was acknowledged, it would just be put under some very general head, in terms that nobody would ever search for. Sorry, I could go on and on about this.

Sae Matsuno (00:37:44)

Yes, so you are talking about the vocabulary use and representation. So misrepresentation has been a problem, but also the omission of certain information. And do you think the bias of library cataloguers plays a part in it or more an issue of a wider society that’s reflected on them? Meta data or a classification scheme… What would be your views?

Vanda Broughton (00:38:24)

I suppose it’s actually really difficult to unpick it. One of the difficulties is the change in language. And I think often here minority groups are a bit at fault, because everybody likes to be called, by whatever they call themselves. And this, this is true. I mean, not just of minorities, it is true. When boundaries change, you know, when countries break up, and, you know, they call themselves something different, they always want to be called by whatever they call themselves. And it’s very difficult to keep up with this sort of thing. I think it’s been particularly difficult to keep up with the vocabulary in areas like sexual orientation, because often what’s, well, two things really, first of all, the vocabulary that, that communities themselves use is probably not adequately represented in a scheme because it moves too fast. Big international law authority, like Library of Congress subject heading, takes years for things to change, and there’s a tension between stability in the authority and responsiveness to user needs. So what goes on in society, generally, is probably not necessarily reflected in these big managed standards. And of course, an additional problem is that sometimes what was an acceptable term to use yesterday may not be an acceptable term today, because the thinking has changed. And I, I can’t think of an example now, but I probably wouldn’t want to use it, even if I could think of something. But people are upset by the use of a term that would have been fine 10 years ago. So it’s a very sensitive area, but one that’s incredibly difficult to deal with, so that the correspondence between sort of managed information sector and society as a whole, it’s quite difficult to maintain a sensible correspondence. So really, the information sector is lagging behind, and what society does, as a whole.

But then there are some quite interesting examples of really sort of appalling misrepresentation or lack of representation even in quite, quite recent times.

Sae Matsuno (00:41:36)

I think it’s very interesting that you’re mentioning the dilemma between natural language that’s changing rapidly and the more systematic controlled vocabulary in a library cataloguing and classification that cannot be as flexible as the natural language development, and all sorts of political contexts associated with a certain term, such as the alien in the library.

Vanda Broughton (00:42:22)