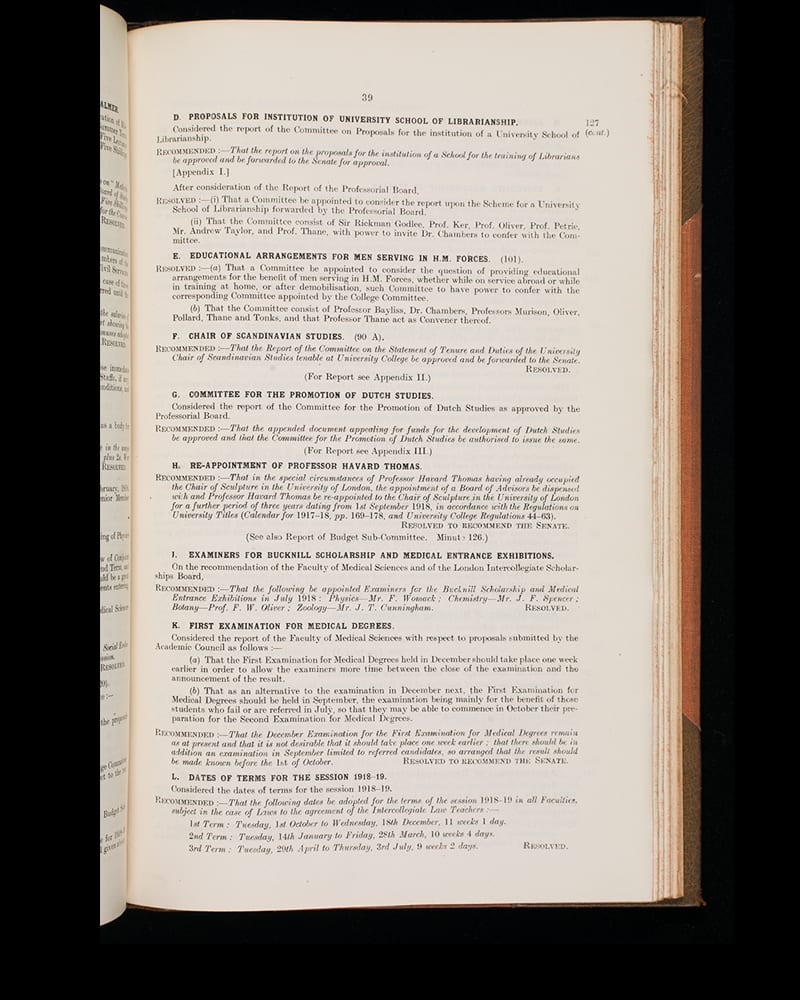

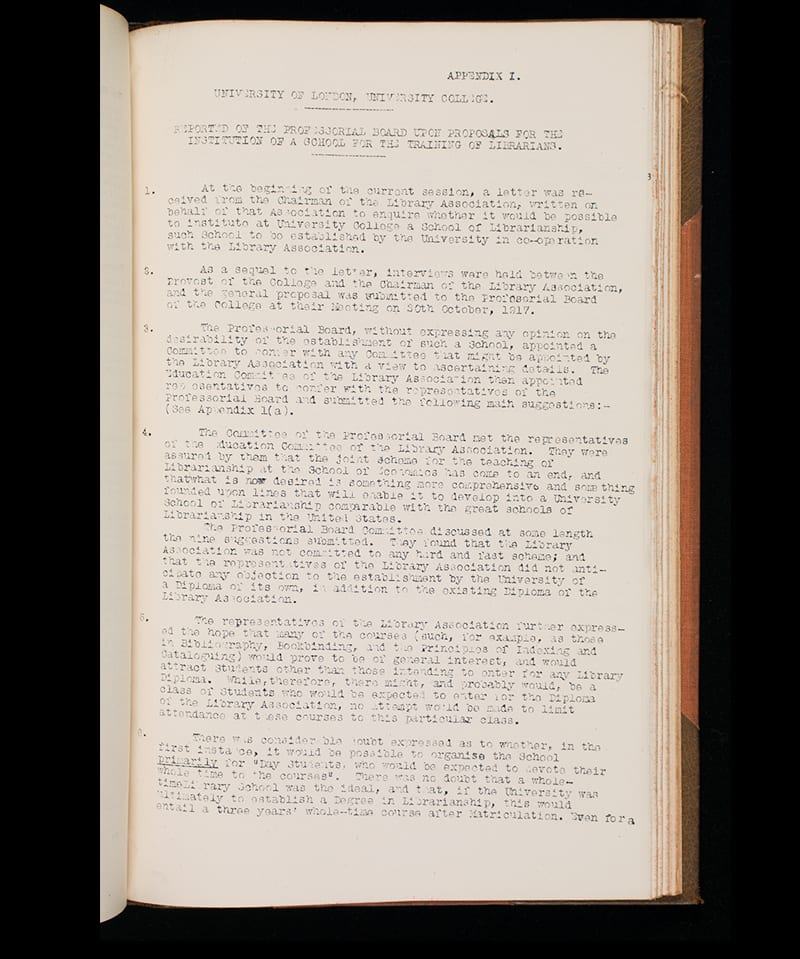

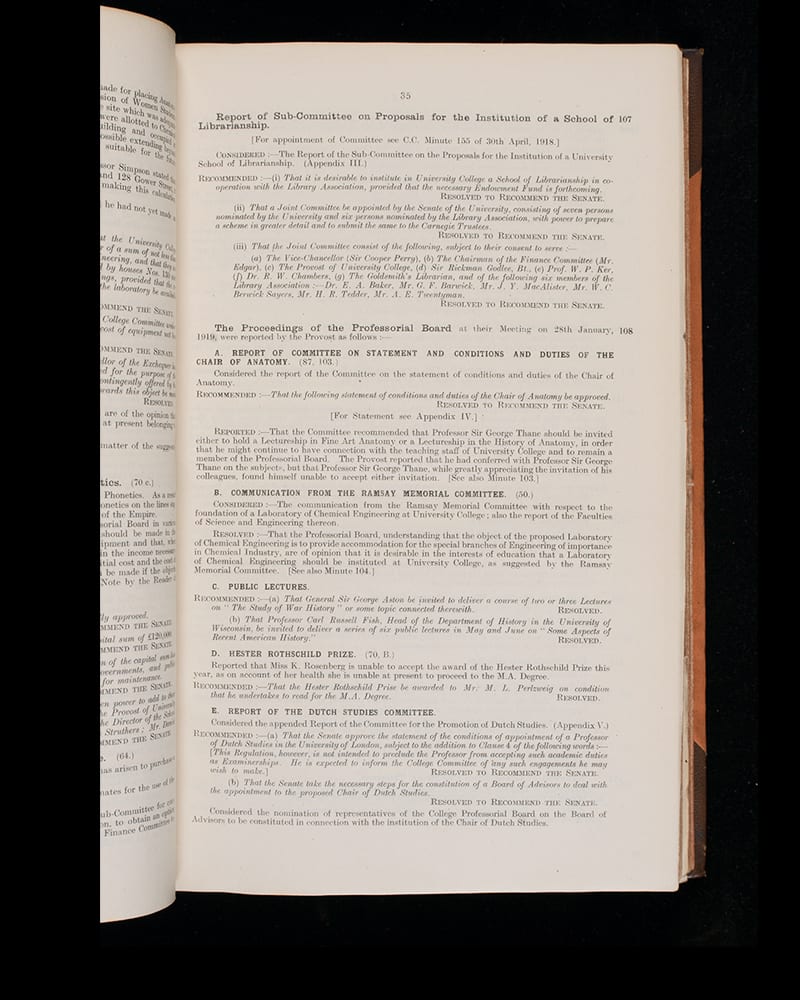

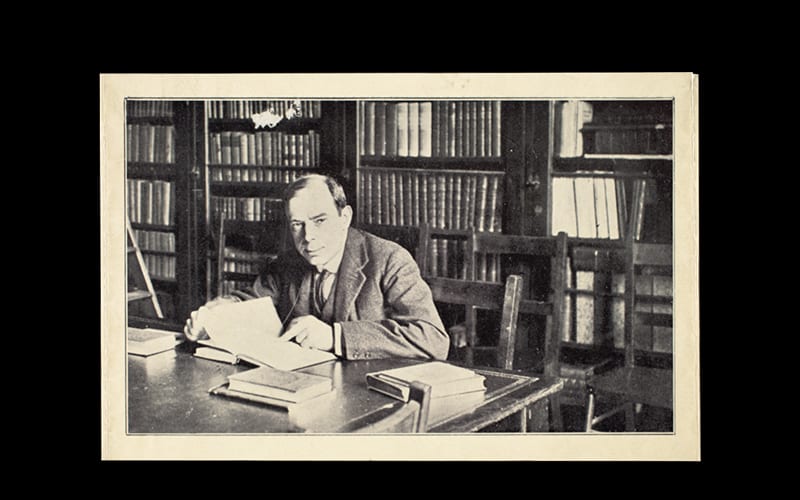

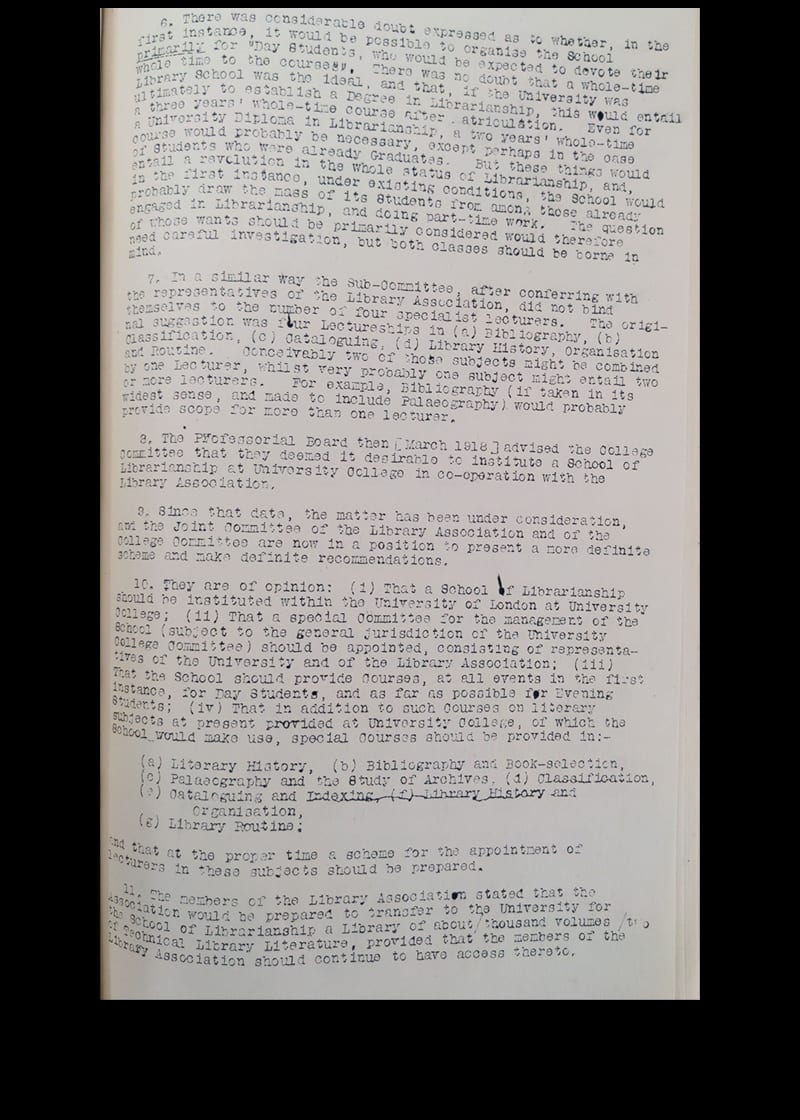

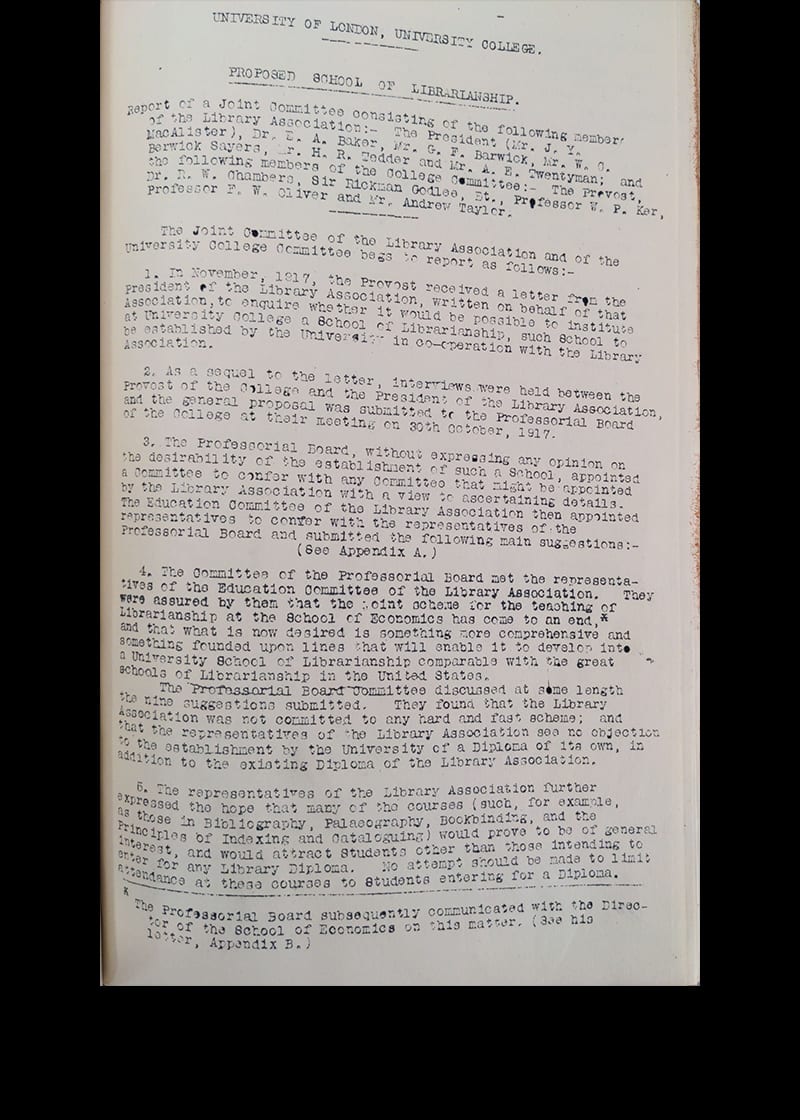

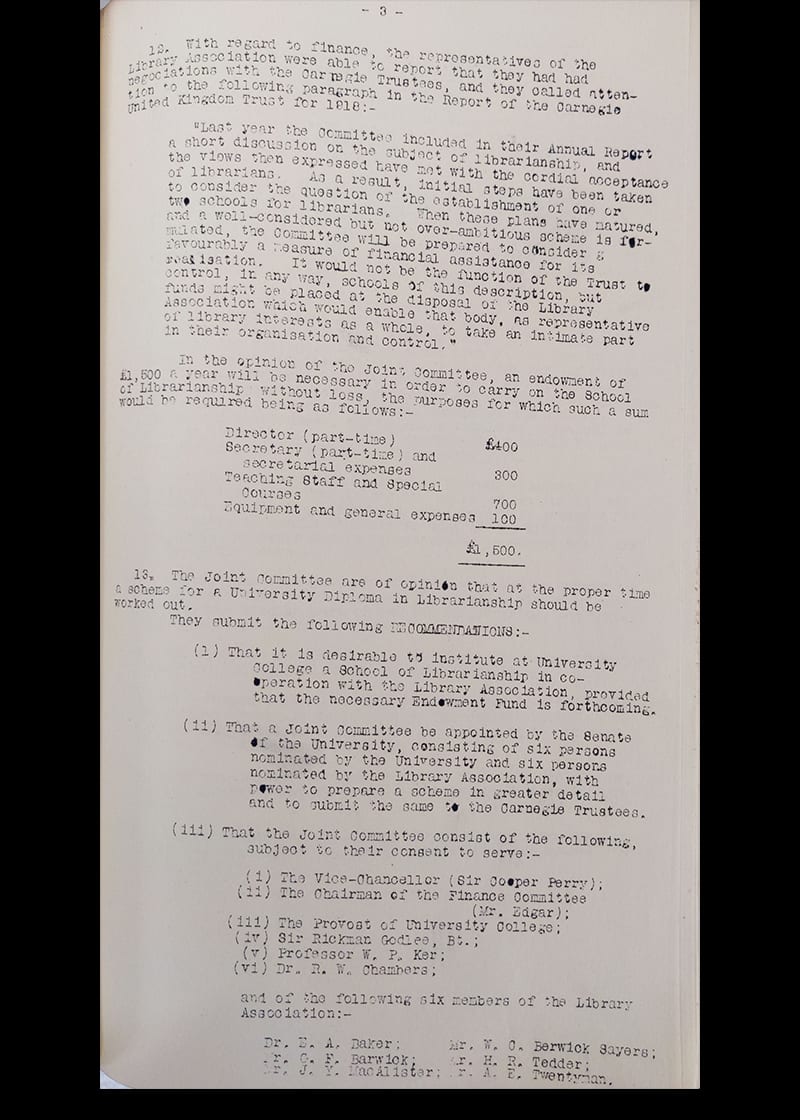

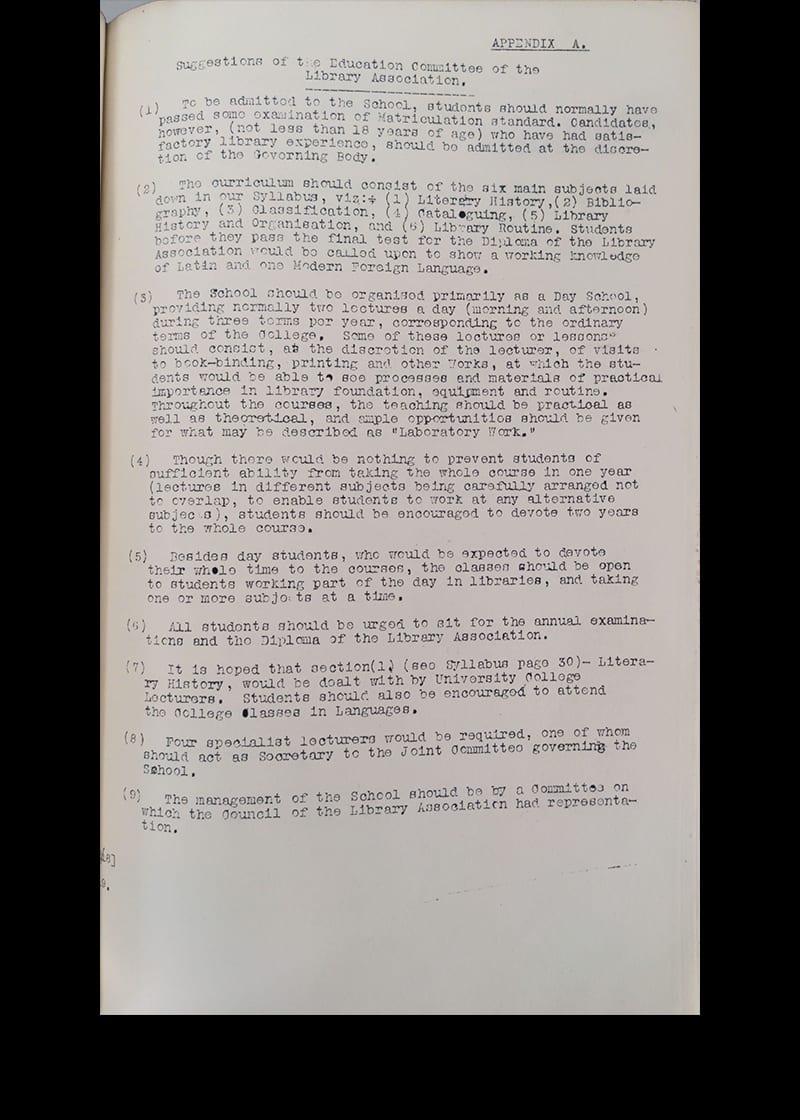

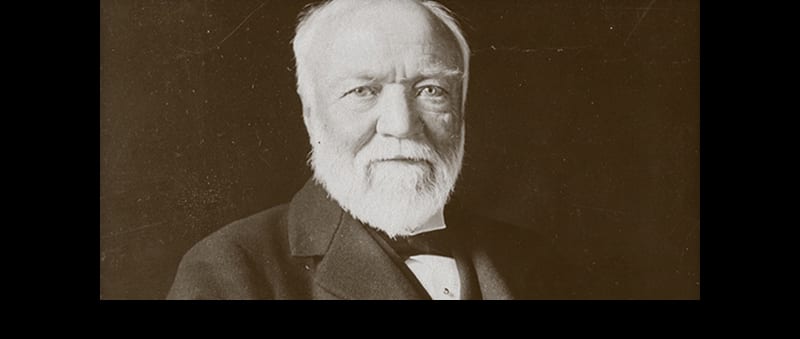

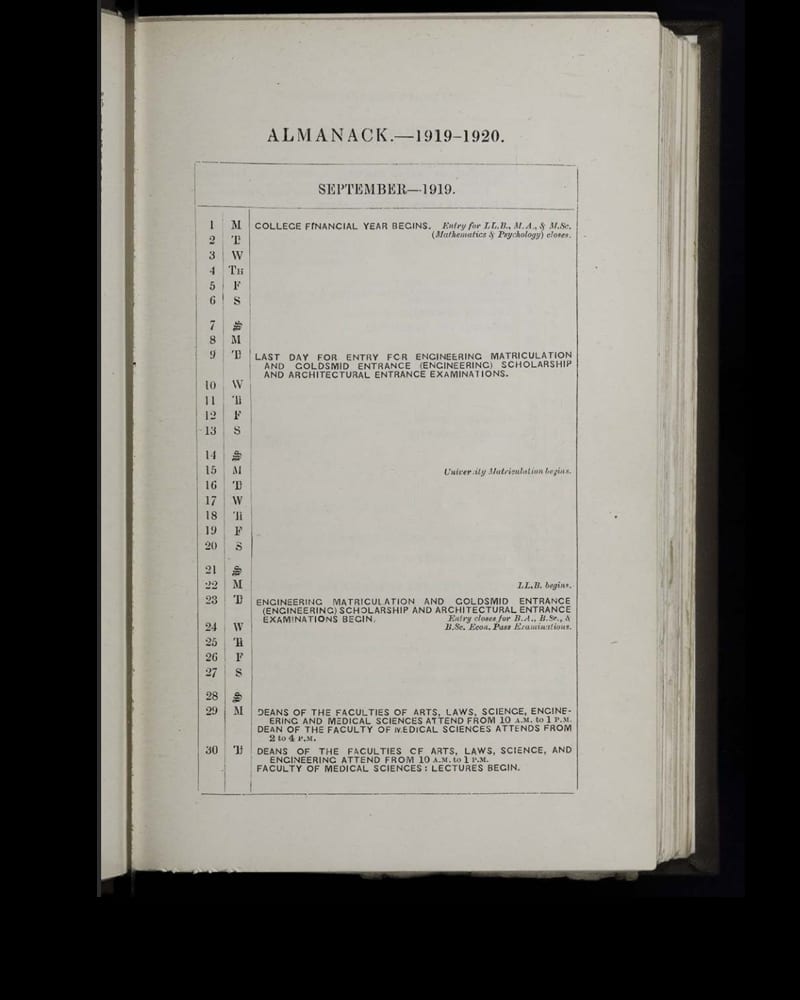

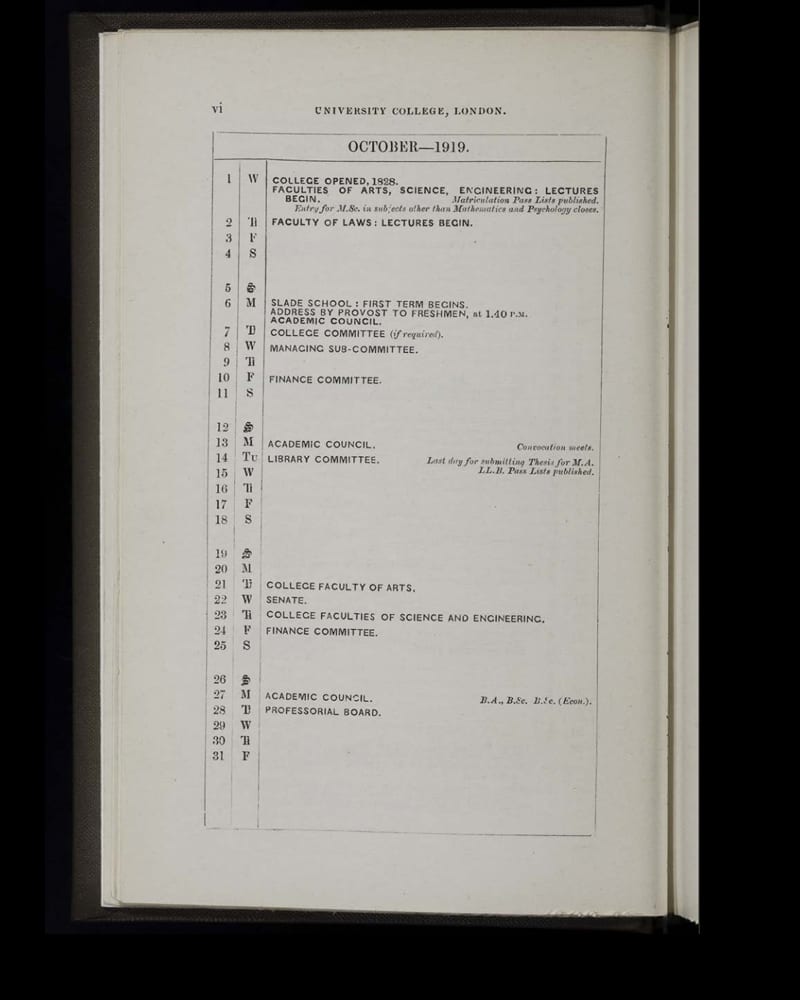

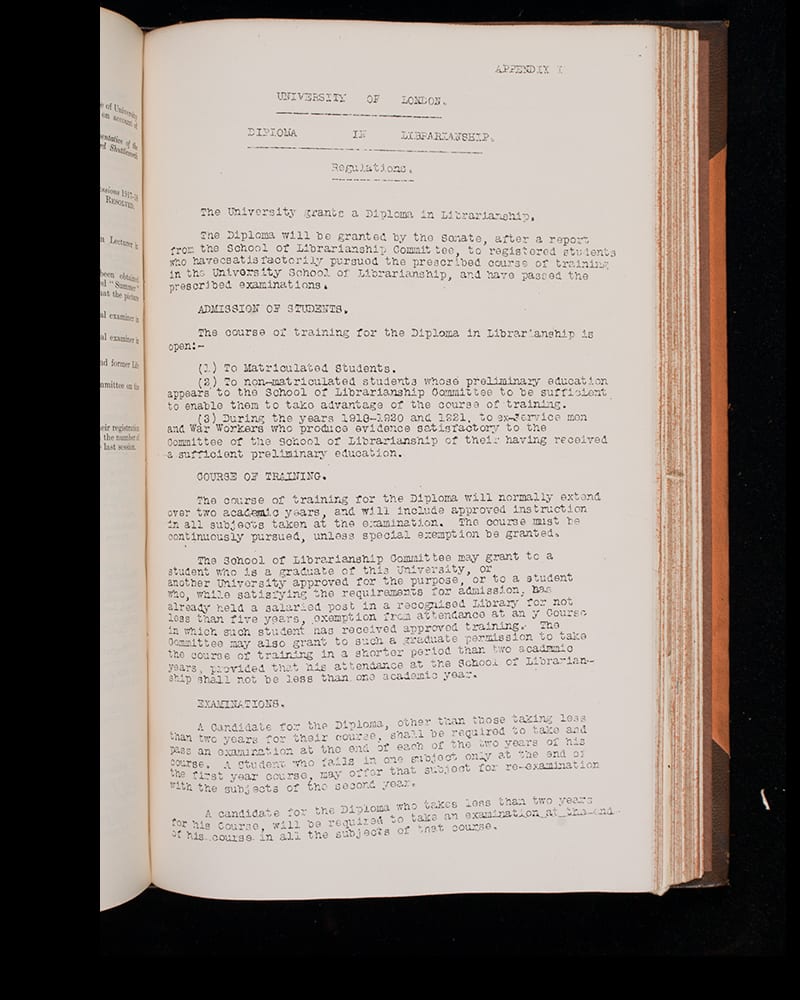

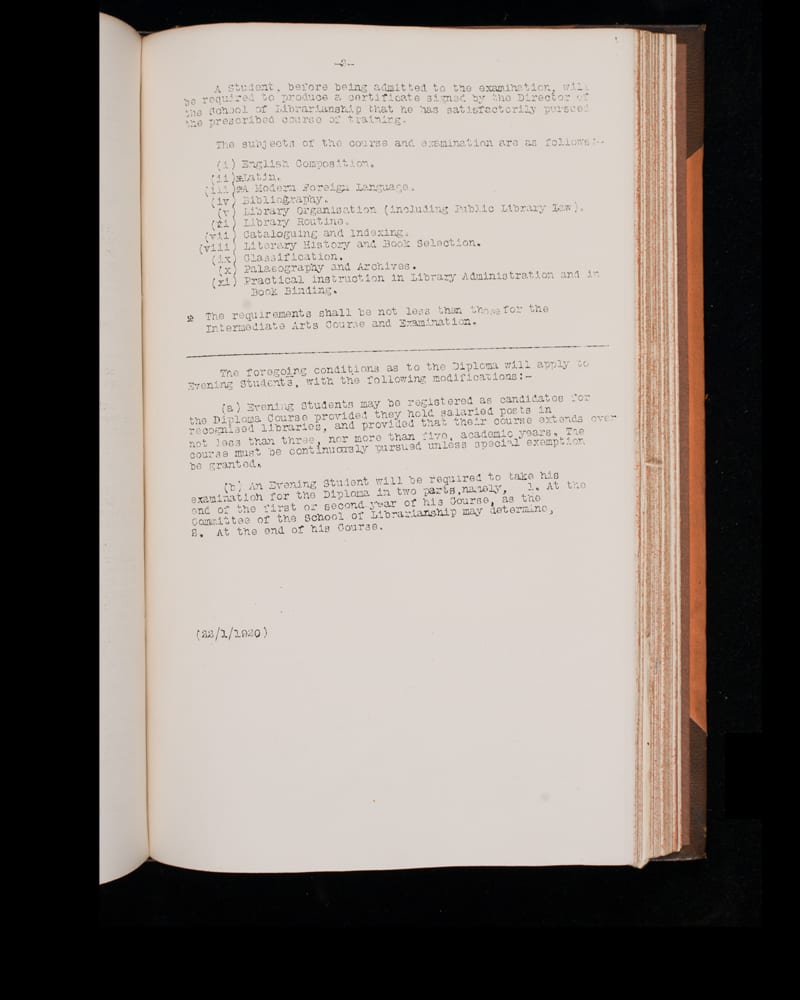

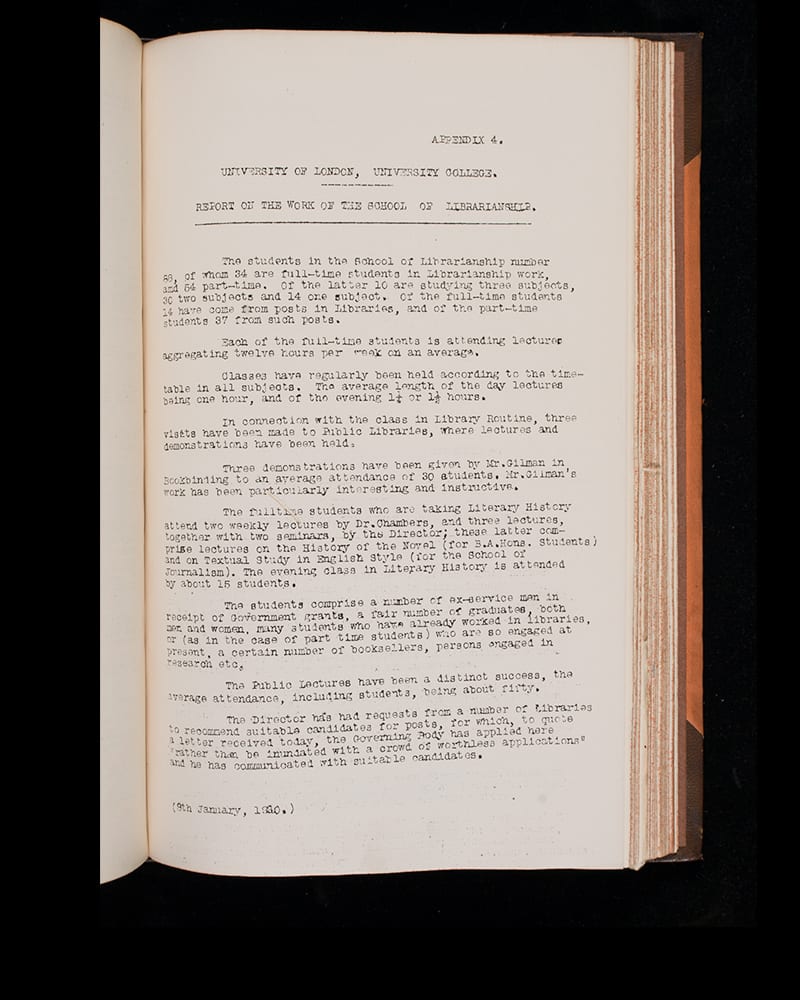

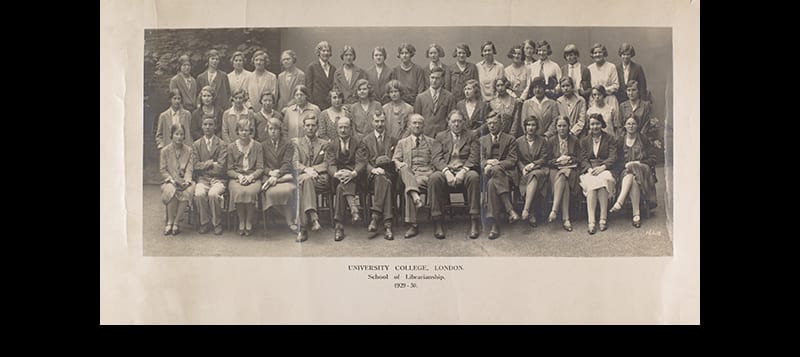

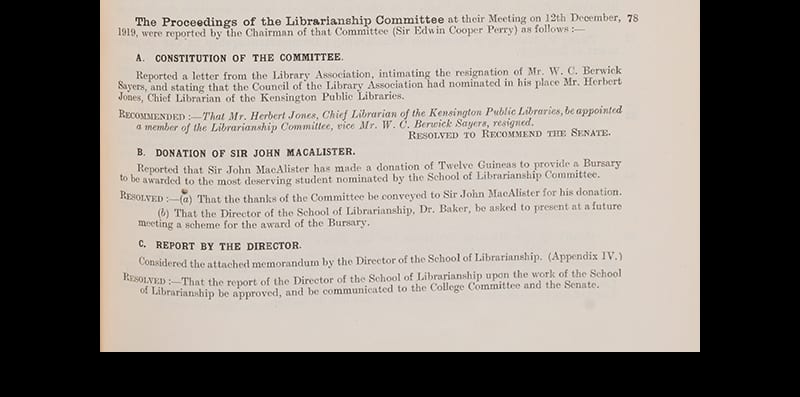

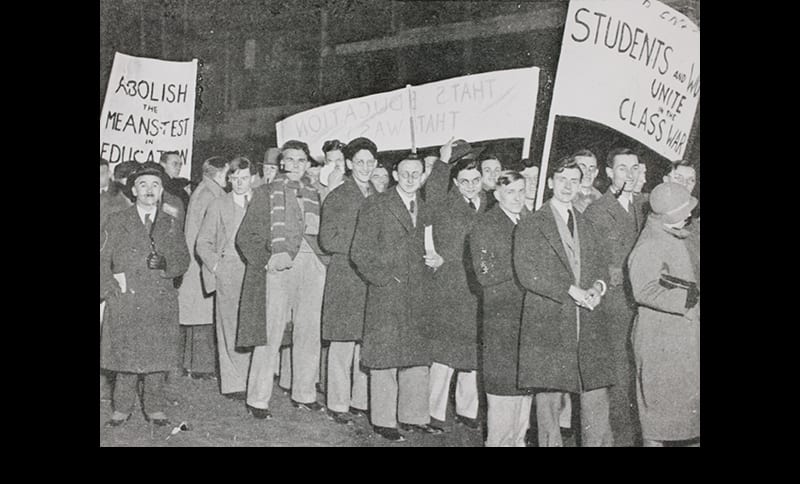

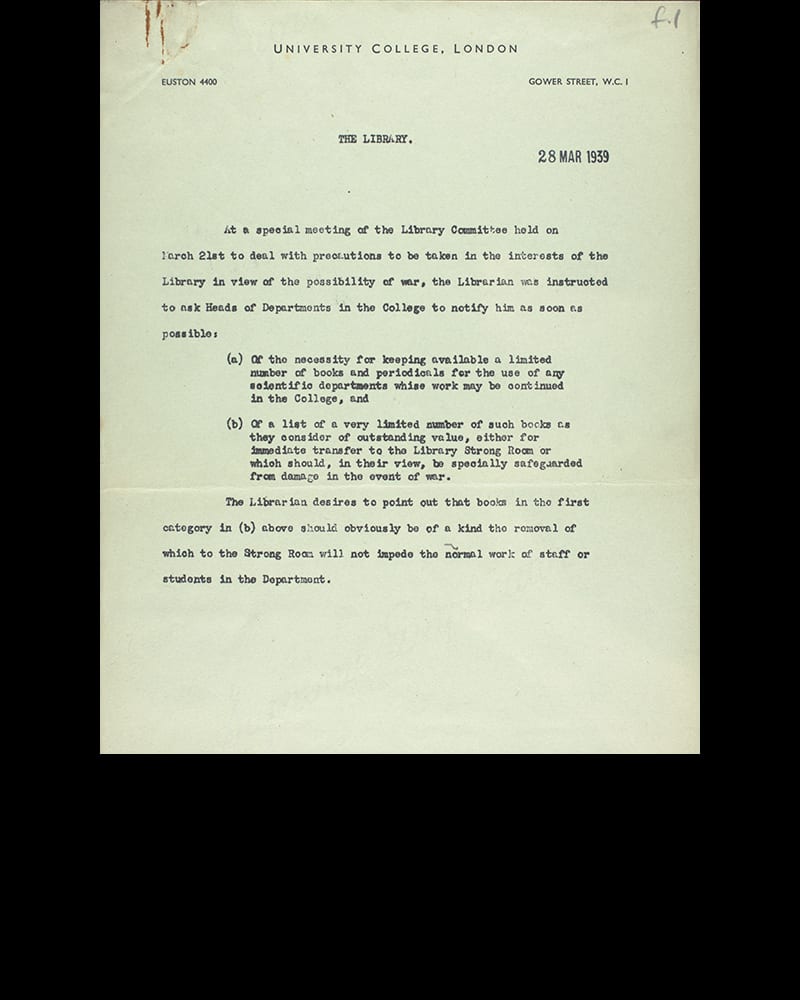

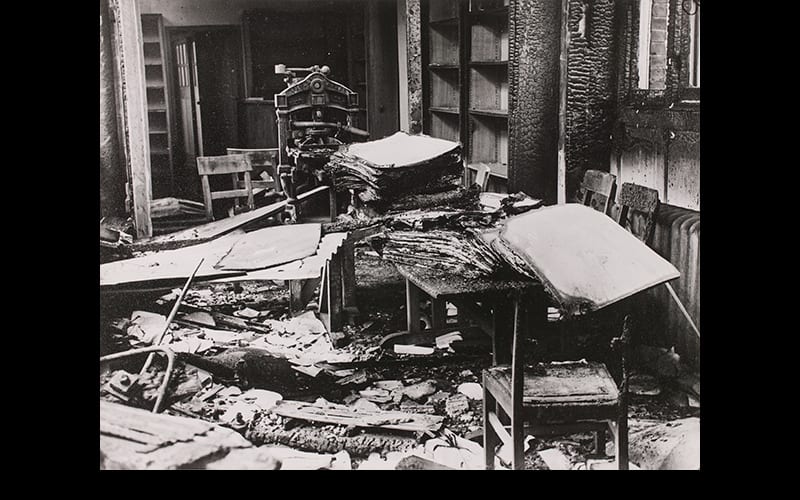

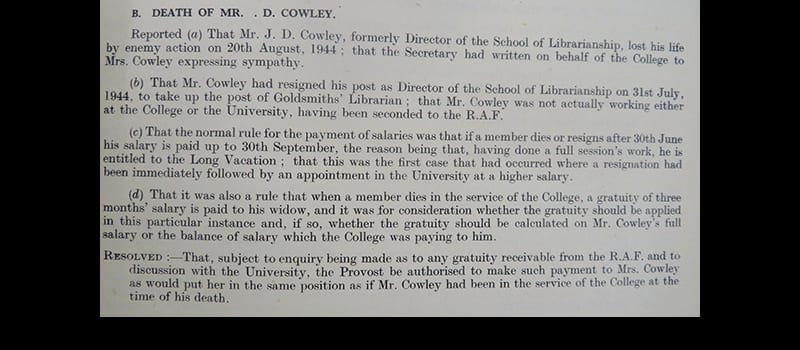

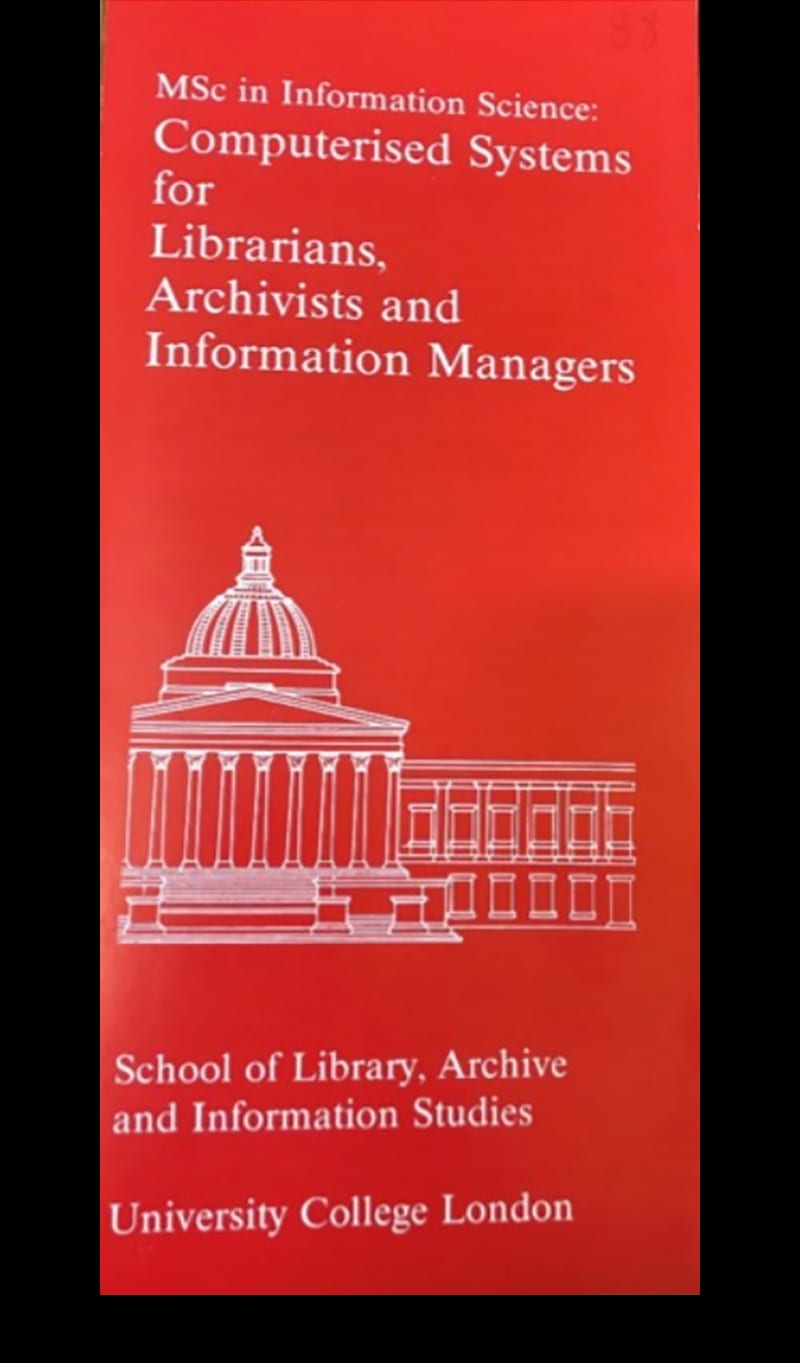

Geographies of Information: Celebrating 100 years of Information Studies is an exhibition marking the centenary of UCL Department of Information Studies. It charts the history of what was known as the School of Librarianship while exploring the role that teaching has played over the past decades in the creation of an international, professional workforce. Starting as the first British School of Librarianship in 1919, the department came about after two years of intense negotiations between UCL and the Library Association. Following its official opening in October 1919, the School of Librarianship began to offer its course in Librarianship to British and international students, paving the way for other Higher Education institutions in Britain and leading training programmes for information professionals in an expanding job market. During the Second World War, the School was suspended with many staff and students leaving the University to join the war effort. The University campus itself was substantially damaged during the London Blitz and it took a few years before the main UCL library opened again.

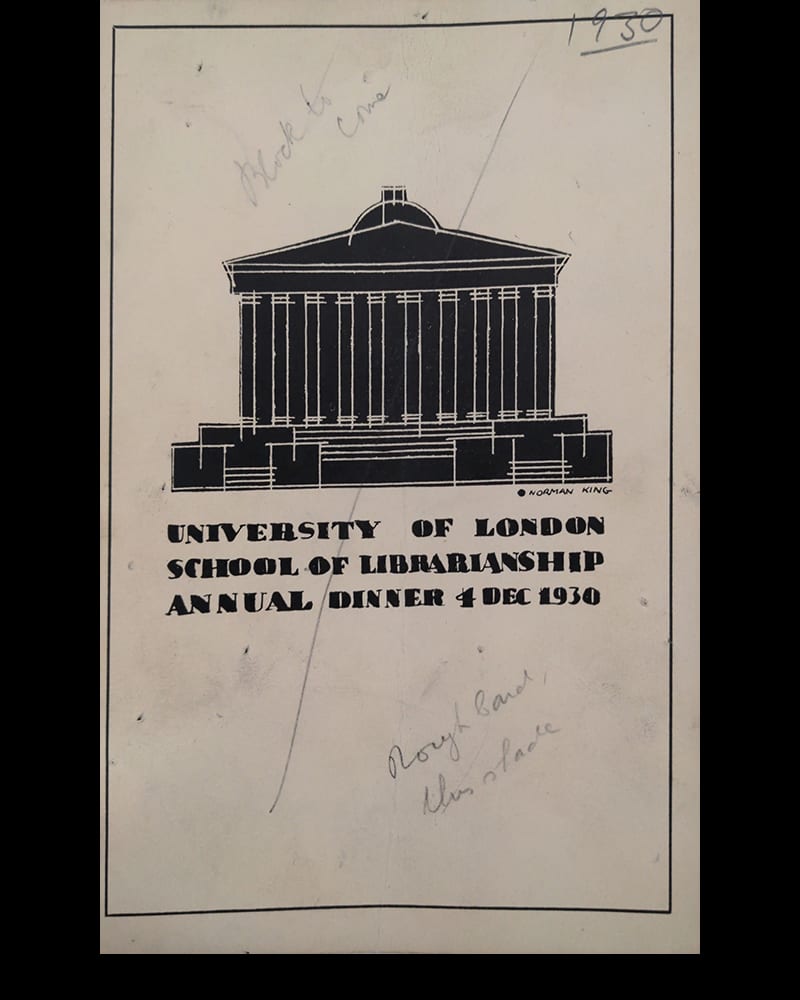

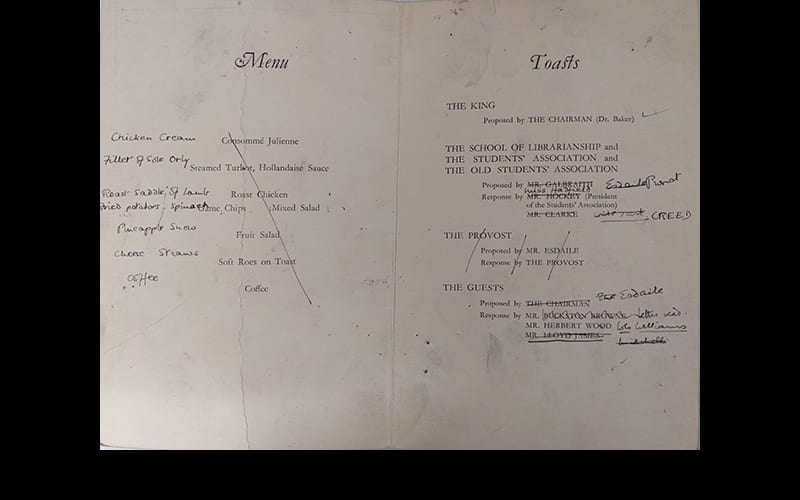

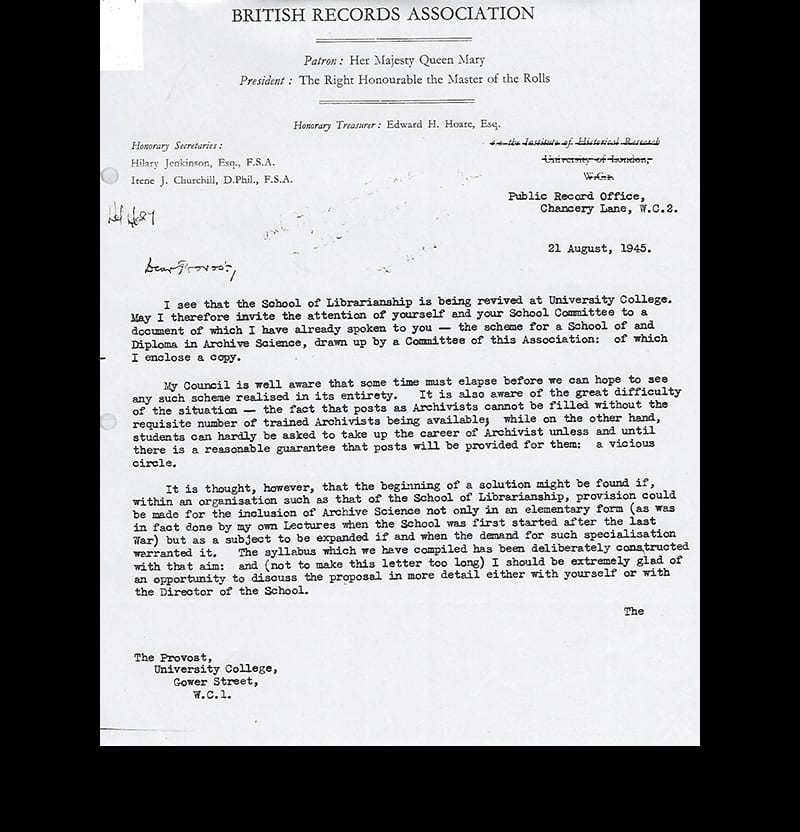

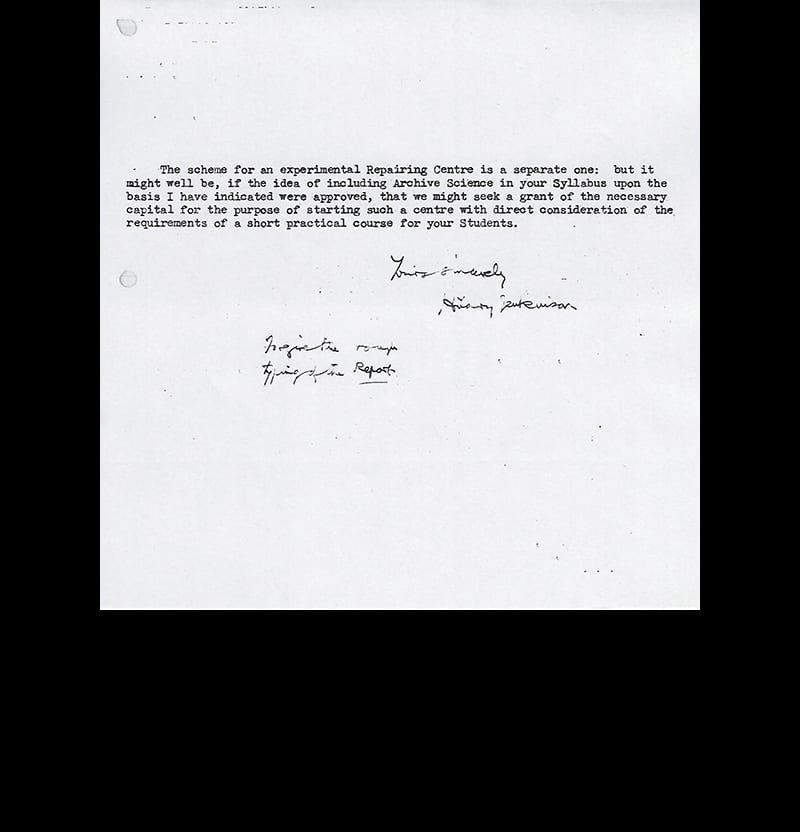

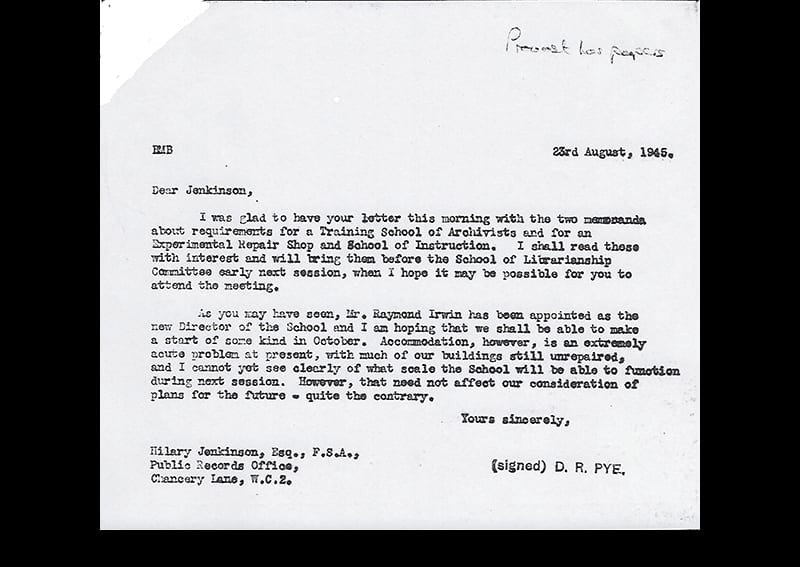

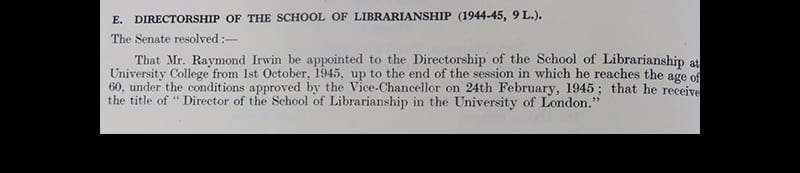

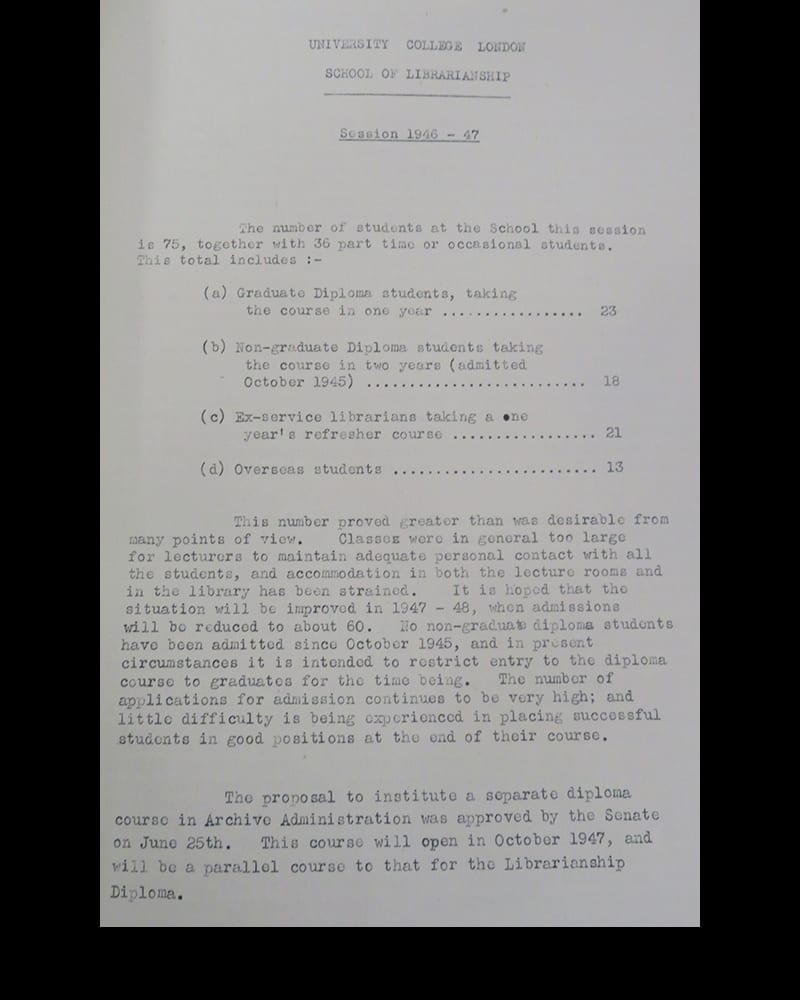

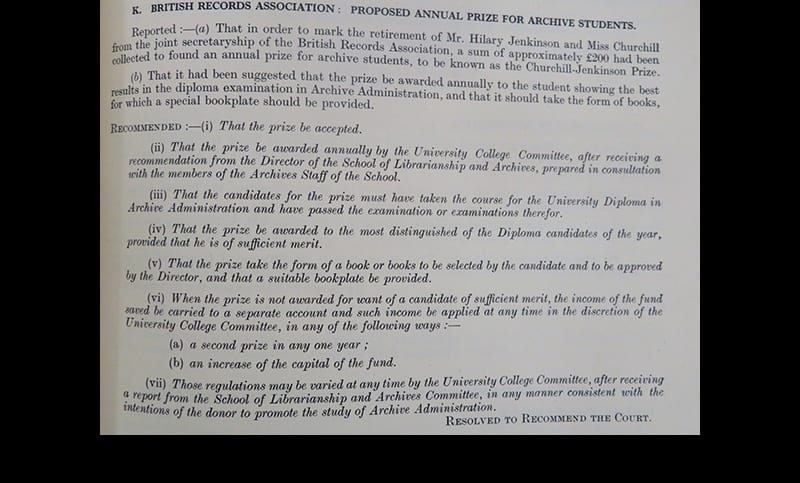

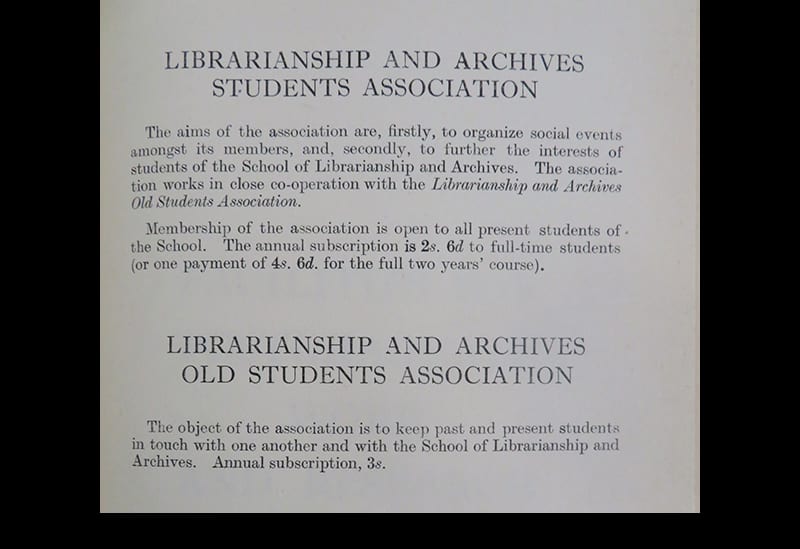

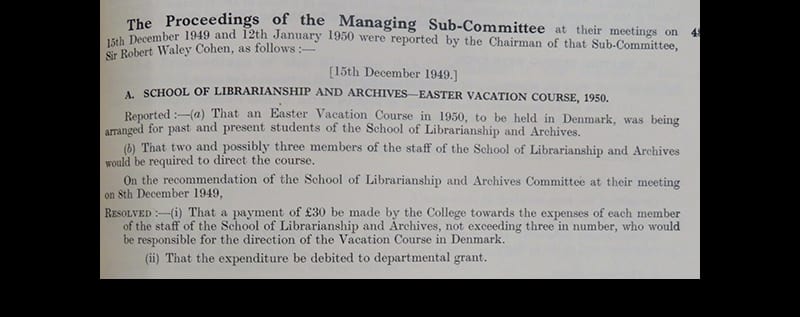

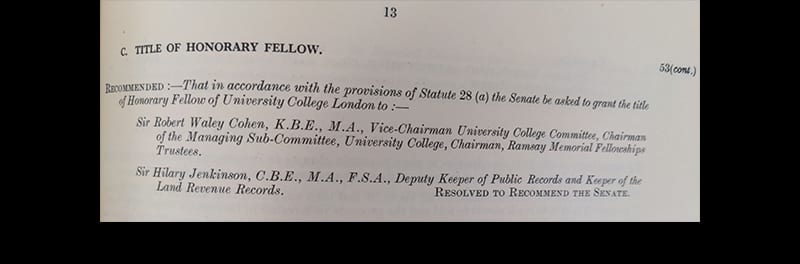

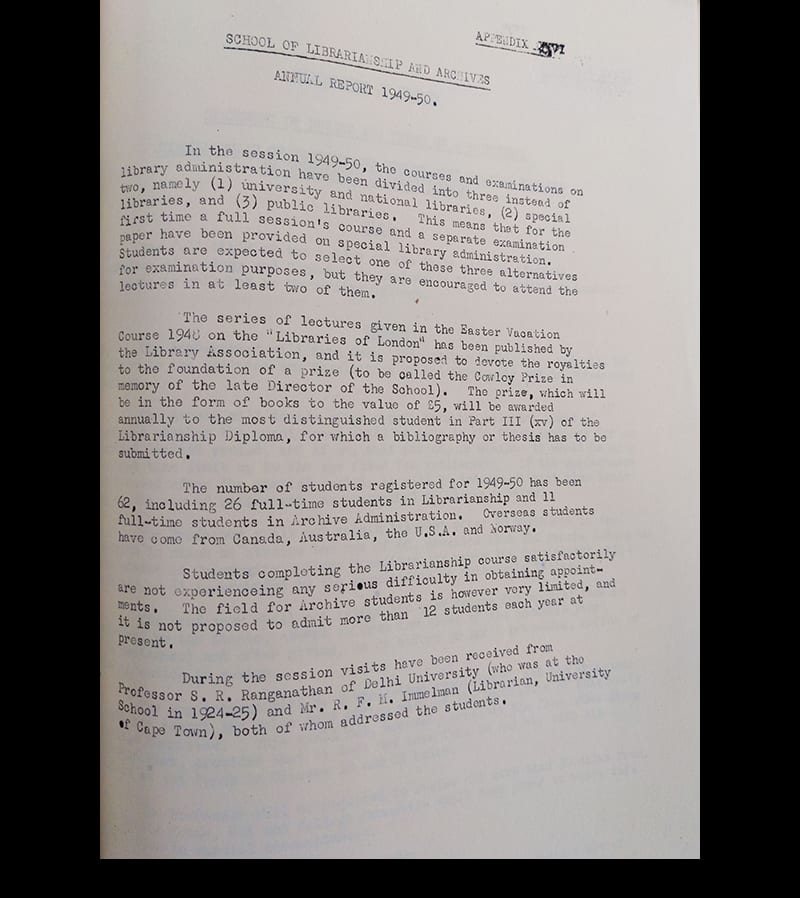

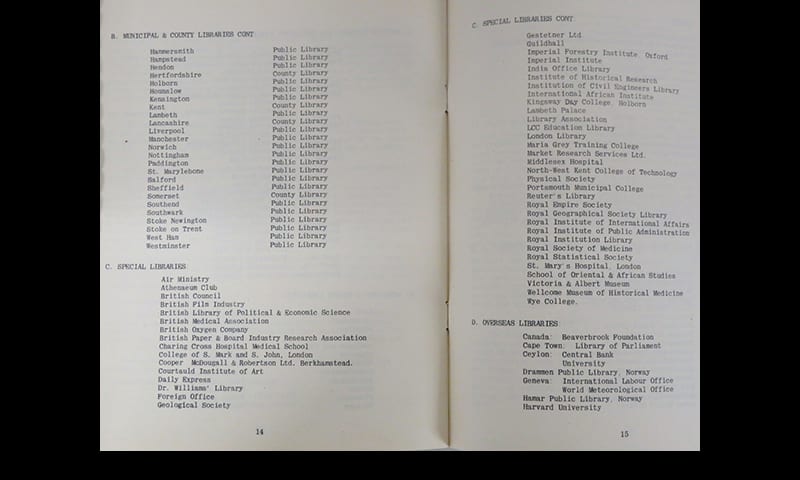

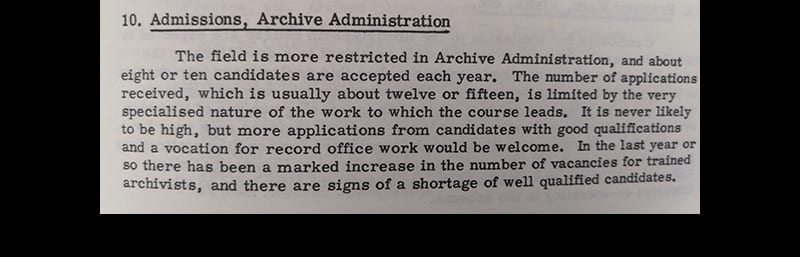

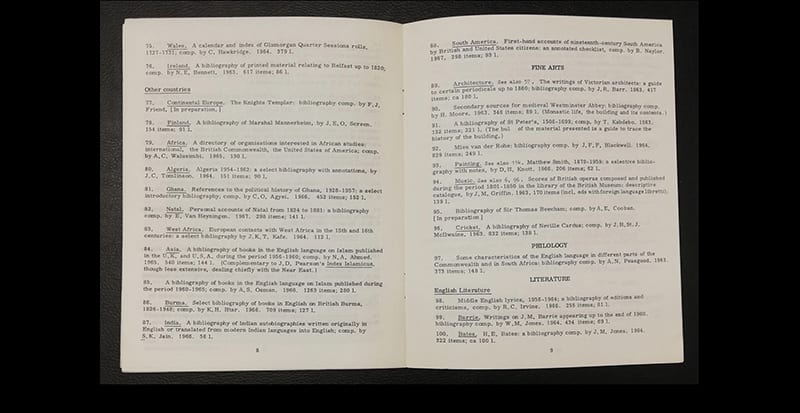

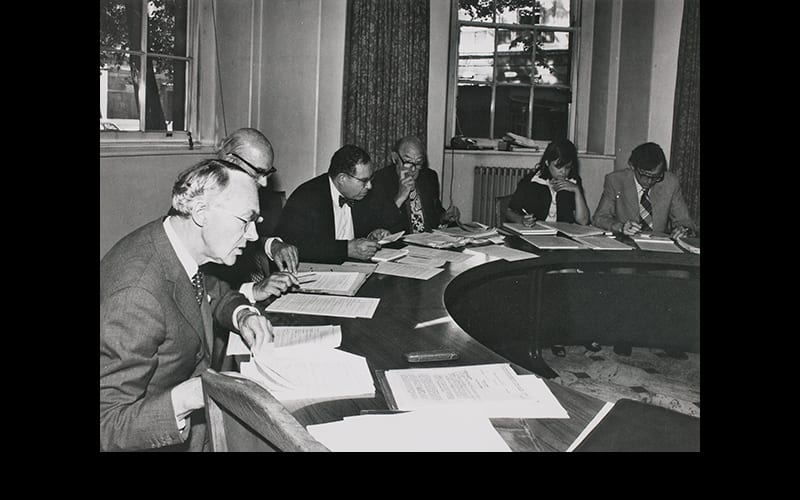

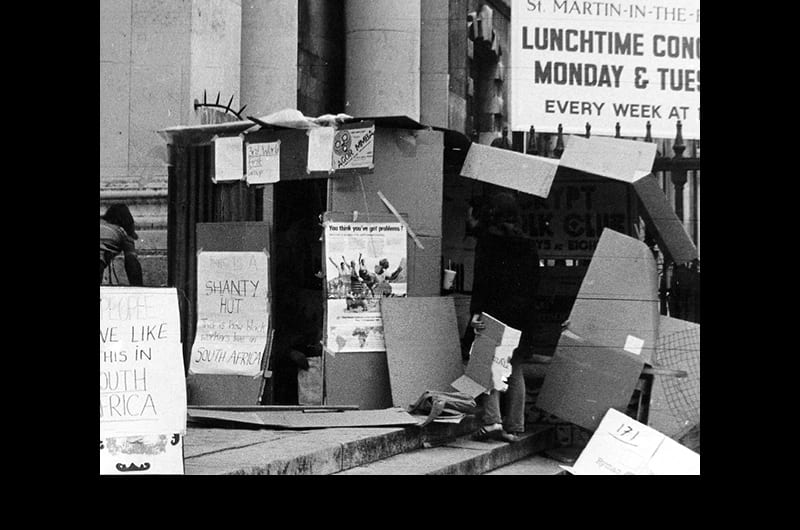

Following the war, the Diploma in Librarianship resumed alongside a new Diploma in Archive Administration, which was eventually established in 1947. By 1960 a hundred students had already graduated from the Archives course. More generally, the success of the School of Librarianship and Archives helped to establish its worldwide reputation, promoting professional standards that influenced information management practices worldwide through an international cohort of students. Moreover, over the decades students developed a number of social activities, which run alongside their demanding academic courses, and are reflected in the publication of a number of student magazines including “The Librarianship Magazine” (1927-1935), “The Link” (1930-1970) and “The Crazy World of Arthur Brown” (1970s).

These publications distributed in-jokes, updates about the course and gatherings, poems, short stories and pub recommendations. In light of this tradition of students’ involvement in the life of the department, when I began my work as Curator of the exhibition, I decided to take the opportunity to design a cross-curriculum learning programme that would allow students to take a central role in the creation of this landmark project, and undertake one-term-long research activity in connection to the exhibition, which also helped embedding the “Connected Curriculum” within the department in line with UCL’s education strategy 2016-2021.

To have integrity and reflect the nature of the work carried out at the department, it became also important to expose students to disciplinary knowledge of scholars and professionals representing the truly global perspective of Information Studies. In line with this objective, I designed an Oral History programme that aimed to engage students with former members of staff and international professionals, reflecting UCL’s ambition to involve students in research and enquiry, exposing them to the latest knowledge and thinking, and creating a horizontal dialogue between staff and students. This dialogical approach is reflected in the design the Virtual Tour section of the exhibition, which was conceived in response to the restrictions imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, forcing me to reconceive the exhibition for the online rather than the physical space. To respect the original plan of presenting the exhibition in the North and South Cloisters of UCL Wilkins Building, I researched a number of online digital platforms that would support 3D showcases to help recreating the experience I had originally envisioned. Soon I realised that the challenge was not so much the reconstruction of the physical space within the digital, but rather to re-think the temporalities of the online experience, embracing the interaction between digital historical artefacts and the stories emerged from the conversations between students and professionals. As pointed out by the race scholar Karen Salt in her keynote presentation to the 2020 biennial conference of the Association of Critical Heritage Studies, ‘practice is a tool to transform and change relationships’. Similarly, my aspiration in designing the exhibition was to establish a new form of relationality, which would be equally as important as the final creative product, presenting me with a challenge that was less about reproducing space, and more about engagement with time. I hope the exhibition you are about to visit will rise to the challenge and engage you in a dynamic and stimulating exploration of the remarkable life of our university department.